Guest blogger: Donald Gill

Donald Gill (2nd from left) with Michael Schaeffer, Michael Lowe and Anthony Rooley at a Lute Society Summer School in 1976

Apart from making instruments such as the Renaissance guitar, vihuela, cittern, orpharion, French mandore, viola de mano and bandora (including one for James Tyler), and playing all of the above, Mr Gill also wrote two small books and contributed a number of authoritative articles to the Galpin Society Journal, the Lute Society Journal and Grove.

The following piece was written in November 2012.

I was very appreciative of the birthday greetings in Lute News 103 [October 2012], though I did not recognize myself as one of the ‘great pioneers’ of the lute revival.

As apparently I am now the oldest member of the Lute Society, I feel that some of my memories should be recorded, but I would have to go back more than the 56 years since the Society was founded for them to mean much.

I therefore go back to around 1931–2, when my best friend at school bought a ukulele, which meant that I had to have one too. My musical activities at that time involved piano lessons, and later, playing the viola in the school orchestra, with no great enthusiasm for either. But when the daughters of a family we were on close friendly terms with, whose father was German, heard of the ukulele they straight away said, ‘Oh, you must get a guitar!’

In those days, nobody knew what a guitar was, except as something vaguely Spanish, but they were familiar to Germans. Somehow I scraped together about 15 shillings [currently equivalent to 75p!] and bought a guitar in a local junk shop, and a copy of the Carulli Tutor, and set about teaching myself.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

I heard the occasional recital by Segovia on the radio, and was very impressed by the vihuela pieces that he played, and this started me off wanting to know more about the vihuela and its history. This led inevitably to the lute, as I had also heard Diana Poulton play on the radio, and started searching for books about the lute, such as they were in those days.

Eventually I acquired an old German lute-guitar from a junk shop in Charing Cross Road, chopped its peg-box off and fitted a reflexed alternative to make it more lute-like and allow for double strings.

Here you can see and hear an unaltered lute-guitar

Lute music was a problem, as none was published in the UK and, in any case, the war came along and interrupted further progress, which had to wait till I got back to Britain in 1948 and began to pick up the threads.

These included contacts with other early investigators who were generous with information and sources of music. I was fortunate to be posted to a London job in 1949, and met Diana Poulton, Ian Harwood and Major Michael Prynne [read Mr Gill’s tribute to him in the 1979 Early Music].

I managed to get together £35 for one of the lutes that Alec Hodson was making – a copy of the ‘Warwick’ Frei. [The famous early 16th century instrument by Hans Frei in Warwick County Museum is arguably one of the finest of all surviving lutes.]

Research was interrupted by two short-notice three-year [army] postings to Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong in 1951–4 and 1956–9, so I was actually in Singapore when I became a member of our Lute Society. I was again fortunate that from 1954–6 I was in a London posting and could resume research, acquiring music, attending meetings in London, and copying British Museum Library sources.

Alemande & Corrente from Partita IV by Filippo Sauli c.1710, transcribed and edited by Donald Gill

My time in Singapore convinced me that lutes would not survive such heat and humidity, and I thought that the orpharion or bandore should be investigated — metal strings and simpler construction — if I was going to be able to enjoy plucking in possible future postings.

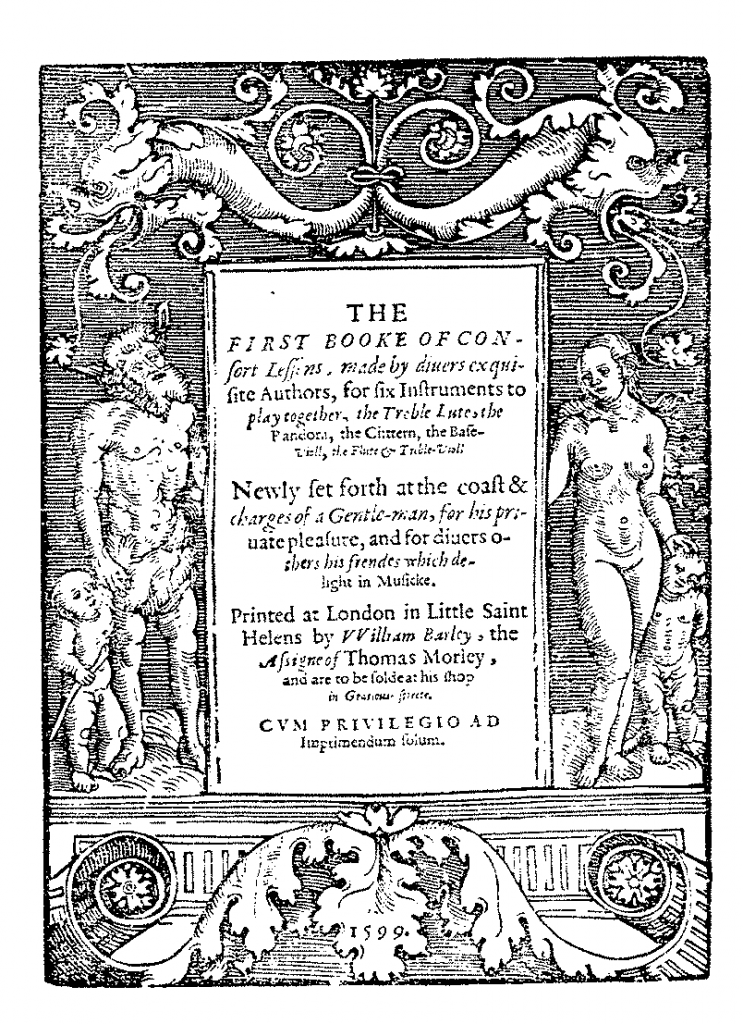

About this time the Morley Consort Lessons were published, which became an added incentive.

[Thomas Morley’s The First Booke of Consort Lessons (1599 & 1611) was arranged for the distinctively English broken consort or ‘consort-of-six’, consisting of three plucked string instruments (lute, cittern, and bandora – called ‘Pandora’ by Morley), two bowed instruments (treble viol or violin and bass viol), and a recorder or transverse flute. This special combination of instruments was reportedly a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I.]

One thing led to another. I found myself wanting to find out about the early guitar as well as the vihuela, and then the small lutes, French and Italian mandores and mandolinos also seemed worth investigating.

This led to curiosity about the big mandoras and gallichons [or gallichones], which struck me as being an excellent alternative to lutes for the technically challenged (such as myself) as well as being a significant part of the whole picture. This coincided with Martyn Hodgson’s independently reporting on the restoration of an example in the Castle Museum, York, and his identification of it as a mandora or gallichon.

I always wanted to know what the music sounded like, and not being a millionaire I made my own sample instruments, starting with a bandora and going on to other instruments such as 4- and 5-course guitars, mandores, mandolinos, and a bell-gittern. Also a couple of vihuelas and a viola da mano, as research progressed.

Three Short Tunes for the Bandora, transcribed and edited by Donald Gill

After leaving the army, and then ten years in Northern Ireland, where some research was possible but an absence of colleagues and meetings was felt, we moved back to England in 1974. I have however been thwarted recently by arthritis and can no longer make or play. If that had not been the case I would have been looking at the guitar and kindred late citterns now, to help fill in the picture.

My memories are more diffuse than specific and are very much coloured by the good nature and generous helpfulness that seems to be characteristic of Lute Society members and helped make our Summer Schools so enjoyable.

There is, however, one specific memory that has stayed clearly with me. One evening I took Major (later Major-General) Michael Prynne in my 1923 Vauxhall open tourer to visit Diana Poulton at her country cottage. The thought of two regular army officers, one a vintage sports car enthusiast, visiting the doyenne of British lutenists, still appeals to my fondness for the unexpected. And the visit itself was a great pleasure, made completely unforgettable by the weather, which was cloudless and warm, with a full moon giving so much light that headlamps were hardly needed. I don’t know what Major Prynne thought of motoring with the hood down, but to me, a long-time member of the Vintage Sports Car Club, it was perfection.

© Donald Gill 2014

Thanks are due to the Lute Society for the photo at the top, to Lute News magazine, where this article was first published, and to Gardiner Houlgate for permission to reproduce the photo of the Alec Hodson lute, which appeared in one of their frequent musical instrument auctions.

Leave a Reply