|

|

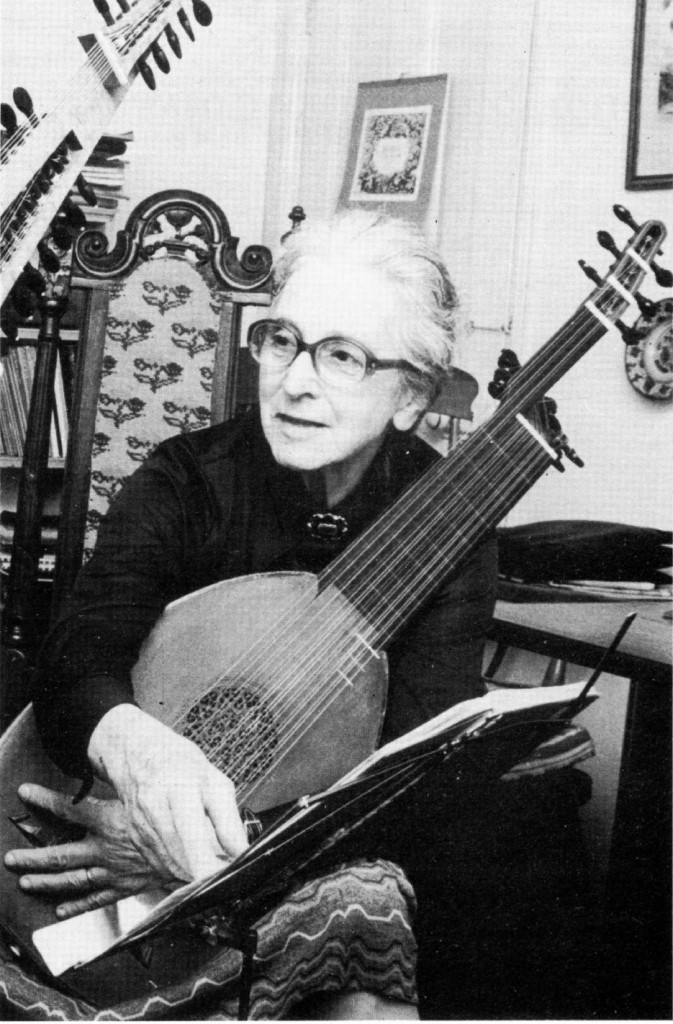

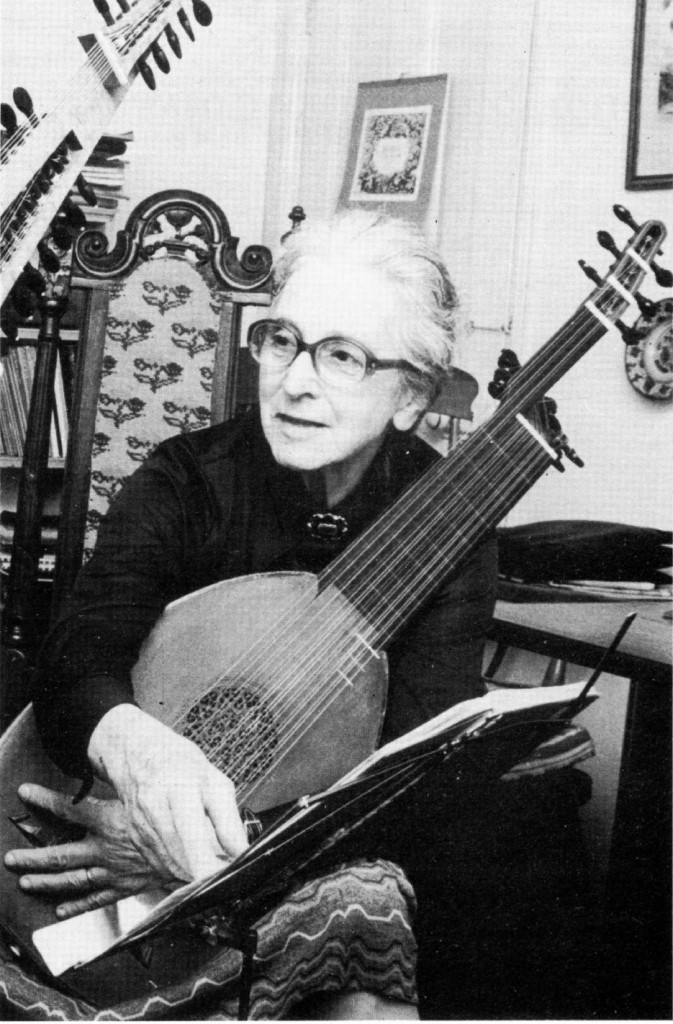

Diana Poulton in her 70s by Guest Blogger: Thea Abbott

Sadly I never knew Diana Poulton (1903–95). She died just one year before I ‘discovered’ the Lute Society and began to understand the crucial role she had played in the revival of the lute and in developing a modern audience who understood the instrument and the sensibility of the music which had been written for it.

Of course it is true that Arnold Dolmetsch himself is the figure most remembered for the renaissance of interest in early music performance in the early 20th century, but without the link provided by Diana Poulton I suspect that it would have taken much longer to establish the wide circle of makers, players and musicologists that we have today in the UK. [See also here]

I have recently published a biography of Diana Poulton, and this short overview gives a few of the details of her life contained in the book, some of which are surprising. For instance, people who felt that they knew Diana quite well (as a teacher and fellow musicologist) have been amazed to read about her membership of the Communist Party of Great Britain and her relationship with a refugee from the Spanish Civil War.

When she was a child Diana showed no sign that she would make a name for herself as a musician; she was originally expected to follow her mother, Ethel Kibblewhite, and her aunt, Dora Curtis, and become an artist. She studied at the Slade School of Fine Arts from 1919 to 1923, but was spirited away from the visual arts when she began to accompany her mother to Arnold Dolmetsch’s recitals in London.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Dolmetsch’s first lute student

She was entranced by the sound of the lute and determined to learn to play it herself. She became Arnold’s first lute student. Her lessons with him were not happy, but when she later began to teach herself her experience of Arnold’s teaching led her to seek out many the original tutors and instruction books which were to be found in the British Museum and elsewhere.

In 1926 she made her first broadcast for the BBC, live from Battersea Public Baths! She never forgot the terror of playing on gut strings in the humid atmosphere of the boarded-over swimming pool.

Peter Warlock

Two years later, when she was preparing for a recording session with the tenor John Goss, he took her to meet his friend, the modernist composer Peter Warlock (Philip Heseltine), at his home in Eynsford in Kent. At that time Warlock was interested in John Dowland and he and his partner Philip Wilson had begun to collect music and information towards a possible “Life and Works”.

Warlock had never heard the lute played and was intrigued and captivated when Diana played for him; in exchange he played the Dowland Lachrimae for her on his piano and she was moved by the beauty and melancholy of the music.

As she and John Goss were leaving, Warlock reached under the bed at the side of the room and pulled out a large box containing his transcripts of Dowland tablature, and gave it to Diana. It was a treasure trove of material which must have taken years to assemble, and which could have been found nowhere else outside the British Museum, certainly not in any published edition.

Fascination with John Dowland

Diana’s biography of John Dowland, though out of print, is still the only one available, and her edition of Dowland’s complete works for lute is unsurpassed even today.

Her fascination with Dowland amounted almost to an obsession, and Paul O’Dette told me a story about a conference in the Netherlands: when he came down to breakfast he overheard a conversation between Diana and the German lutenist Michael Schäffer.

Schäffer was telling Diana a dream he had just had in which Dowland had been performing when one of his lute-strings broke. Schäffer immediately offered him a spare nylon string. Sadly he had woken up before Dowland had been able to give any opinion of the strange material. O’Dette said that Diana had become very excited and kept asking Schäffer, “What did he look like?” Unable to accept Schäffer’s answer that he just didn’t remember, she went on asking, “But how tall was he? What colour were his eyes? Surely you remember something!”

Most of today’s most influential lutenists studied with Diana at some time, from Anthony Bailes to Chris Wilson and from Jakob Lindberg to Paul Beier. They all tell delightful stories about their lessons in her Islington house, recalling the cats, her generosity with instruments and manuscripts, and above all her wonderful food – garlic-studded lamb, beef in red wine, chocolate and prune cake are often mentioned.

When Anthony Bailes was a young and very hard-up student travelling to London from his home in South Wales, he was particularly grateful for the meals which enabled him to extend his lessons with Diana for several hours, rather than just the one or two hours for which she charged him.

In 1956 Diana Poulton and Ian Harwood (who was 28 years younger than her) co-founded the Lute Society. The association began with just 20 members, including Carl Dolmetsch, Desmond Dupré [lutenist of Alfred Deller], Michael Morrow [director of Musica Reservata] and Robert Spencer, and today has over 1,000 members from all around the world.

© Thea Abbott 2013

Thea Abbott, Diana Poulton: the lady with the lute, is available in hardback, direct from the publisher, Smokehouse Press, £15.00 plus postage and packing.

Also of interest:

The Dolmetsch Family with Diana Poulton: Pioneer Early Music Recordings, volume 1 (See blog post) Recordings, mostly from the 1930s, of Arnold, his third wife, Mabel, their children and musical friends playing small ensembles and viol and recorder consorts by the Lawes brothers, Purcell, Dowland, Marais, Leclair and others. This CD is not available in record shops, but you can order it here.

The recently restored organ built by Johann Wöckherl in 1642 for the Franziskanerkirche in Vienna © Bwag / Commons I was very pleased recently to come across a copy of the Vanguard LP – issued on the Amadeo label – made in May 1954 which, apparently, was this group’s first recording played on historical instruments, albeit with modern bows and strings.

It’s an all-Bach programme, with Cantatas numbers 170 and 54 and the Agnus Dei from the B Minor Mass, which according to Pierre-F. Roberge of www.medieval.org became something of a “cult” recording.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by email.

In an interview, Gustav Leonhardt recalled:

Because of the strength of the dollar, the American companies had found out that they could come to Vienna and record for almost nothing. So they swarmed there in droves, and I met the people of the Bach Guild [Vanguard], for whom I made a lot of records.

This was not the first time that Deller and Leonhardt had worked together, as they had previously made a live broadcast, for Dutch radio in April 1952, which was happily recorded and is now online.

Although all the tracks from this record have been reissued on CD, there’s something rather special about having the original, with its simple stylized church window on the white sleeve and a more spatial analogue quality to the sound.

This predates the Leonhardt Consort days; and the group was called the Leonhardt-Barockensemble back then. The billing on the sleeve suggests that Eduard Melkus rather than Leonhardt’s wife, the violinist Marie, led the single string band, but maybe this was simply because his name was better known at the time. (I’ve always been puzzled as to why Melkus never went over to gut strings and, as a consequence, his fame as a Baroque specialist became eclipsed by others who did make the change.)

The other players were Alice Hoffelner (the future Mrs Harnoncourt), Kurt Theiner, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Alfred Planiawsky and the oboist Michel Piguet.

The texts of the cantatas are printed on the back of the sleeve, and there’s a blurb – in German – about the music, but nothing at all about the musicians. Curiously, Deller is described as a “Tenor (Altlage)” [alto range], as the term ‘countertenor’, revived for him by Michael Tippett, had at that stage not made it to Vienna. For more on Deller’s career, see my blog post.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt described his experience of Deller as follows:

We had never heard a male alto before, and now this! A magnificent sound, handled with refinement, effortless, light, ideal for our old instruments; exceptionally individual and used with great expressiveness. To accompany him was sheer pleasure.

The recording was made in the Franziskanerkirche, described on the sleeve as having “world-renowned acoustics”. It is no coincidence, however, that this church also contains the oldest organ in Vienna, built by Johann Wöckherl in 1642. This instrument is used to great effect by Leonhardt and I particularly liked his playing, and the chirpy registration, in Wie jammern mich doch die verkerhrten Herzen, below.

Leonhardt said of the recording: “Deller was superb, we were atrocious;” while Marie Leonhardt remembers:

Deller sang the Agnus Dei beautifully, and we accompanied him on three baroque violins that sounded as out of tune as a crow [translated from the Dutch kraaievals]. Whenever I hear this record, I just want to die of shame.

Despite its flaws, this record was an important milestone, and must have sounded strikingly different from anything else that was on offer almost 60 years ago.

Copyright © 2013 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

Christophe Rousset + Les Talens Lyriques – Wed 21 August 2013 – The Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh by Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

One of the greatest treats for me – and for all Baroque music lovers – at this year’s Edinburgh Festival was the three memorable performances by French harpsichord virtuoso Christophe Rousset on no fewer than six of the instruments in Edinburgh University’s Raymond Russell Collection. There were two solo recitals in St Cecilia’s Hall, the home of the Collection and Edinburgh’s oldest (and most elegant) purpose-built concert hall, and a morning concert with members of his band Les Talens Lyriques in the Queen’s Hall.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Rousset is as much at ease with delicate, reflective works where emotional intensity springs from rubato and inégalité as with flashy, rattling display pieces. In each case, the music chosen and the style of playing were sensitive to the demands and possibilities of the instrument. So sensitive, in fact, that the instruments themselves, brought gloriously into voice by Rousset’s playing, threatened to steal the show.

The Russell Collection is the core of the university’s large collection of early keyboard instruments. It was gifted to the university after Raymond Russell’s death in 1964. St Cecilia’s Hall, dating from 1763, is Scotland’s first purpose-built concert hall. A link to the catalogue of all the instruments in the collections is here.

St Cecilia’s Hall and the Russell Collection are intimately linked, and the instruments rarely leave their home, so it was particularly exciting to see the exquisite Goermans/Taskin harpsichord on the stage of the Queen’s Hall with Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques. This instrument (see the soundboard painting here), originally built in 1764 by Jean or Jacques Goermans, French harpsichord-makers of Flemish origin, was much altered in 1783 by Pascal Taskin, the foremost Paris maker at the time. Rousset himself singles it out as “the jewel of the collection”. See the whole instrument here.

Christophe Rousset talks here (on video) about playing the Russell Collection’s harpsichords

More beautiful even than the famous Taskin harpsichord of 1769, probably the most widely reproduced harpsichord in the world?

Well, Rousset doesn’t specifically say so in the interview above, but the 1769 instrument featured in his second solo recital in works by Rameau and Claude-Bénigne Balbastre (1727–99) and hectic encores by Pancrace Royer, music teacher to the daughters of Louis XV.

The Goermans/Taskin, though, was the perfect vehicle for the refined, deceptively simple textures of François Couperin’s seventh Ordre, especially the velvety lower register Couperin uses to heart-wrenching effect. I was ready to agree with John Kitchen’s programme note:

The textures, ornamentation and many other subtle aspects of French harpsichord music, and arguably of Couperin’s in particular, are inextricably bound up in the sound and touch of contemporary French harpsichords. The music cannot be played convincingly on any other instrument – not even on 18th-century harpsichords from other traditions.

A musical “cake shop”

Other instruments being tasted in this musical “cake shop”, as Rousset calls the Collection, were:

- an Italian virginals of 1586 by Alexander Bertolotti, surviving in almost original condition and playability; used for a group of pieces by Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583–1643);

- an anonymous Italian harpsichord of 1620 or thereabouts, originally with an enharmonic keyboard – splitting the G sharp and E flat keys in the middle octave – but subsequently updated by Bartolomeo Cristofori (inventor of the piano) or one of is pupils; used for four lesser-known Scarlatti sonatas (K34, 450, 308, and 309);

- a 1755 harpsichord by Luigi Baillon, who may have been born in Italy but who seems to have incorporated both French and Saxon features into his instrument; used for a spectacular sonata (H32) by C. P. E. Bach;

- an English harpsichord (1709) by Thomas Barton which also combines Italian and English styles; on this one the elfin Rousset gave us works by J. J. Froberger (1616–67), Louis Couperin (c. 1626–1661), and Henry Purcell.

While the differences in sound and timbre between the plangency of the early instruments and the fuller sound of the 18th-century harpsichords were clear, those between the several 18th-century machines were subtler, but still detectable.

For instance, John Kitchen notes a contrast between the luscious fullness of the Taskin and the less rounded tone of the Baillon harpsichord used for the Bachs (J. S. and C. P. E.): the latter, with a reedier tone than the typical Parisian instrument of the time, would have sounded more familiar to Bach, and was perfect for the F sharp minor Prelude and Fugue from Das wohltemperirte Clavier II, where its less rounded tone let the fugal structure speak out.

It was truly wonderful to have the opportunity to hear all these important instruments in excellent playing order. The pleasure was only increased by Rousset’s introductory remarks as he moved smoothly from one instrument to another, giving both him and the audience a moment to “change gear” into a different playing style and listening mode.

The series of performances, and the restoration of the instruments to good playing order, were generously supported by Dr George & Mrs Joy Sypert, who are to be heartily thanked for choosing the Collection as the focus of their benefaction and enabling so many of these “wondrous machines” to be played to such a virtuosic standard.

I, for one, hope that these important instruments can be seen more often beyond St Cecilia’s Hall, and that perhaps recordings of Rousset playing them will be forthcoming to re-cement the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France!

Listen now:

A programme of music by Purcell, Couperin, Rameau, and Froberger from one of these concerts, recorded for the Early Music Show by the BBC.

© Mandy Macdonald 2013

Rudolph, Cécile and Arnold Dolmetsch recording a Dowland lute song (www.semibrevity.com) The Dolmetsch Family with Diana Poulton: Pioneer Early Music Recordings, volume 1 (published by the Lute Society in association with the Dolmetsch Foundation) is an important historical document for anyone who’s interested in two generations of early music pioneers who were active before the Leonhardt/Harnoncourt era even began.

PLEASE “LIKE” THE BLOG (ON THE RIGHT), & NOT JUST THIS PAGE

This CD is also a small homage to Diana Poulton (1903–1995), lutenist, founder of the Lute Society, editor, and biographer of John Dowland. Poulton was the first person in Britain to make a serious study of the lute. She primarily taught herself, had three years of tearful lessons with Arnold Dolmetsch (described in the sleeve notes as “a very irascible teacher”) and then continued her researches into original sources at the British Museum, encouraged to do so by Rudolph, Arnold’s mild-mannered and brilliant son. For a fuller account of her life, see this appreciation.

Interestingly, a Dolmetsch lute, reportedly made for her, has just turned up at an auction in New Zealand. See here.

The recordings are taken mostly from 78s issued by Dolmetsch Gramophone Records between 1937 and 1948, with two additional tracks from the Columbia series History of Music through Eye and Ear, which was produced around 1930. I stumbled across this CD while checking out original 78 rpm recordings of the Dolmetsches on Worldcat. Some master acetate discs were offered online, and I was curious to know to what extent these had been issued commercially (many early Dolmetsch recordings – including the 1929 full set of the Brandenburgs – were never released). Given the scarcity of the original 78s and the historical importance of these performances, I was surprised to see that only one library (in Buffalo, New York) has this CD.

Arnold, his third wife, Mabel, their children and musical friends play in small ensembles and viol and recorder consorts by the Lawes brothers, Purcell, Dowland, Marais, Leclair and others. The extraordinary basso profundo of Artemy Raevsky and the “natural” voice of Cécile Dolmetsch are featured on several tracks, Arnold plays William Byrd’s pavan and galliard “The Earl of Salisbury” on the clavichord, along with the first movement of Beethoven’s “Moonlight” sonata, on a piano of 1799. There are also several compositions by Arnold himself: three are in “early” style, but his Easter hymn for tenor, piano, organ, violin and violone sounds nothing like what you would expect.

The sleeve notes give full details of the record labels and the original 78s plus tantalizing information about other old recordings, some of which may be issued in a second volume.

I’m writing about this now, as I have a feeling that this CD is known only to members of the Lute Society and dedicated Dolmetsch aficionados, and it deserves to be heard by a wider audience.

This CD is not available in record shops, but you can order it here.

Copyright © 2013 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

Guest blogger: Dr. Jed Wentz (Flutist and operatic conductor, founder of Musica ad Rhenum, teacher at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam.)

One of the joys of working on the STIMU [Foundation for Historical Performance Practice] symposium entitled Much of what we do is pure hypothesis: Gustav Leonhardt and his early music has been to discover just how subtle and consistent the thought processes of Leonhardt were over the course of his performing career. Indeed, he showed a marked difference to those in the early music business who believe they know what authentic performances should sound like.

Leonhardt was quite different, and although adoring fans were happy to see in him the reincarnation of J. S. Bach, he himself stressed, over and over again, the hypothetical nature of early music performance practice. That he offered solutions to problems presented by the music of the past to performing musicians of today is beyond question; that he found a musical language that spoke to generations of music-lovers in a profound way is almost a platitude; but that he himself realized the fragility of the entire early music construction is much less well understood.

The STIMU symposium brought to light just how great a difference there was between Leonhardt’s thought and that of the ‘authenticity’ movement on which American musicologist Richard Taruskin heaped so much scorn in the 1990s. Our intent was to explore the earliest portion of Leonhardt’s career (up until the presentation of the Erasmus Prize that he and Nikolaus Harnoncourt received in 1980 for the Bach cantata cycle), as well as to showcase the latest research into the Northern European repertoire he so loved: that of Sweelinck to Bach.

The symposium opened with a showing of the Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach by Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet, introduced by the American musicologist Kailan Rubinoff. The theatre was full and the film made a deep impression on the audience, though it is by no means an easy one to digest.

Early Influences

The first session of the symposium examined the conflicts between the early music approach of Concertgebouw conductor Willem Mengelberg and the Naarden Circle (who founded the Dutch Bach Society in the 1920s in order to present Bach’s Matthew Passion as a liturgical, rather than as an aesthetic, masterpiece). Presentations by Frits Zwart and myself worked in tandem to compare this early material: Zwart played examples from Mengelberg’s very passionate and Romantic Matthew Passion performances and explained his philosophy of early music, which was not informed by notions of authenticity.

My own contribution examined Leonhardt’s musical education at the hands of Anthon van der Horst, who at that time conducted the Dutch Bach Society. Van der Horst, in contrast to Mengelberg, had a liturgical and ‘authentic’ approach to Bach’s music. In the course of the lecture I also presented new information about Leonhardt’s period at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, including a discussion of his master’s thesis. I argued that the Basel period was most notable for Leonhardt’s in-depth study of J. S. Bach’s notation, as well as for the discovery of much earlier repertoire (early Renaissance polyphony and monophony) in performances led by one of the founders of the Schola, Ina Lohr.

The second session of the day invoked the post-Basel period, in which Leonhardt’s career began to take off. Nicholas Clapton presented fascinating evidence of the influence that the English countertenor Alfred Deller had on Leonhardt, comparing recordings both artists made in order to draw conclusions about Leonhardt’s famous ‘rubato’ technique.

His lecture was followed by that of Kailan Rubinoff, who presented Leonhardt’s early career in the context of 1960s Dutch politics, the rise of new-fangled ‘hi-fi’ sound systems and the radical, historic events that shook the world in 1968.

The afternoon ended with a round-table discussion, led by Leo Samama, in which Ton Koopman, Menno van Delft and Richard Egarr summoned up memories of Leonhardt as teacher and source of inspiration.

PLEASE “LIKE” THE BLOG – ON FACEBOOK, ON THE RIGHT – AND NOT JUST ON THIS PAGE

The North German School

The second day of the symposium, which was curated by Dutch musicologist Pieter Dirksen (who has published important works on both Sweelinck and J. S. Bach), was devoted to the study of the works of composers from the so-called North German School. Dirksen and Stephen Rose examined the works of Georg Böhm; Lars Berglund and Geoffrey Webber explored Italian influences of Baltic composers and on Buxtehude; and Ulf Grapenthin (who gave a moving personal testimony of Leonhardt as colleague and source of inspiration) and Peter Wollny looked at Johann Adam Reincken’s work and influence.

These presentations all looked at stylistic characteristics of the music Leonhardt had so loved, and they hypothesized about how musical styles were transmitted from country to country and between composers, during the course of the 17th century. Michael Maul however, in the first presentation of the day, revealed new information from the archives of the Thomasschule in Leipzig that undoubtedly will have ramifications for the one-to-a-part theory of Bach’s choral works. Leonhardt himself was violently against the one-to-a-part theory, and would certainly have been pleased to know that an important new contribution to the debate was made during a symposium dedicated to his legacy.

Leonhardt’s career

The final day of the symposium saw a return to the theme of Leonhardt’s career.

It began, however, with a lecture by Thérèse de Goede which showed how the study of hexachords and the contemporary rules of voice-leading can result in fresh and exciting performances, a perfect example of how theory and practice can go hand and hand to create exciting music-making.

In the afternoon, Martin Elste, of the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung PK, Berlin, talked about the differences in conception of the harpsichord in the work of Wanda Landowska and Leonhardt, giving each performer their due without judging one or the other.

Gaëtan Naulleau spoke of the Bach Cantata cycle and its influence, and exposed some of the clever marketing techniques which would eventually steer the course of the entire early music industry firmly towards ‘authenticity’.

In what was surely, for many in the audience, the highlight of the afternoon, John Butt gave a thrilling talk, in a typically virtuosic fashion, on the larger context of the early music movement, and proposed its best way forward.

I also presented a selection of film footage drawn from the Dutch Television archives. [Leonhardt was shown, in his very early days, playing continuo while someone else conducted; playing in a children’s programme of fairy tales and in a Saturday night variety show – wearing tails – after the BBC Toppers (famous for the Black and White Minstrel Show) had performed a pseudo eighteenth-century dance routine. Finally, we saw him being interviewed at home, looking slightly ill at ease, in the early seventies.]

This was already an embarrassingly rich programme of events, but there was more: Johan Hofmann and Kathryn Cok both presented hour-long Summer school events, the former about a reconstruction of Sweelinck’s harpsichord and the latter on little-known Dutch basso continuo sources. Both of these topics would have interested Leonhardt deeply.

Summing up

As I mentioned above, the symposium was meant both as a retrospective of Leonhardt’s career and influence, and as provoking thought about the future of the early music movement. But here, once again, Leonhardt was ahead of us. He himself had thought about the way forward. When he told a friend and former student in 2010 that he wanted all of his recordings to turn to dust, he did so because he believed that it was for the good of the movement itself: he had no desire to become an icon, and in so doing, become an obstruction between a new generation of performers and the works themselves.

Leonhardt knew that the masterpieces of the past must continue to be approached directly, not through the medium of editors or interpreters, no matter how great or revered such editors or interpreters might be. He understood that the way forward lies not the preservation, but in the destruction, of the immediate past.

No matter how great the legacy of Leonhardt, imitation is not the path before us.

Here’s a video of Leonhardt playing the harpsichord that he used in his last concert in Italy.

© Jed Wentz 2012

© Semibrevity 2012

Last week I sampled two small slices of the Emma Kirkby master class, on Purcell and his predecessors, held for two days at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam.

The second was much more to my taste, as it was undiluted by the extensive coaching of the instrumentalists which spoiled the first day, and sometimes left Emma with nothing to do. To all intents and purposes, the second session was a singing lesson, which is what it was supposed to be. Lovely.

Emma, charming and polite to a fault – always beginning with “ Sorry, …” – obviously knows this repertoire inside out, and it showed, even when she was not that familiar with a particular piece.

Hearing her sing even a snatch of melody in her immediately recognizable, undiminished flutey tone, was pure joy; and seeing how she could help others to make this music really speak was quite extraordinary.

PLEASE “LIKE” THE BLOG – ON FACEBOOK, ON THE RIGHT – AND NOT JUST ON THIS PAGE

Her comments about where to breathe, singing from your core, and her emphatic and exemplary Italian and French pronunciation were as appropriate as you would expect. In each case, Emma understood completely what was going wrong and knew instinctively what to suggest. It was striking how much changed in the students in the course of the class.

Creating the right mouth shape is key, as was shown in Barbara Strozzi’s Le Tre Grazie a Venere, the all-girl trio with a rather racey text, in which the merits of clothes and birthday suits are compared. Though still “half-cooked” (Emma’s description), and accompanied in the rehearsal room on a Taskin copy, it was a delight, and just got better with each repetition.

Pulling a face, though, even for your art, comes at a price. I was reminded of hearing Emma speak previously about the horrific snapshots taken of her in full flight, where – as ever – she was focusing on getting the right sound and making sure the words were understood, rather than being early music’s poster girl.

As one of the students commented, it is all about expressing the meaning of the words, and not just singing the music on the page. Obvious, really.

In everything she said, Emma was very kind, encouraging and supportive of the choices made, even when rather artificial-looking French rhetorical hand movements – which seem currently the flavour of the month here – threatened to scupper otherwise good performances.

Of course it is very hard to change the way in which you’ve practised a piece. Standing stock-still won’t work either, as was ably demonstrated in a Purcell number about a jilted lover. “An angry, complaining hand by your heart, makes it easier to sing”, she said.

The rule, with movements – according to Emma – is eye … hand … voice, and going with what feels natural.

Speaking of the same piece, she also said “ take time over these ingredients”.

Although she is a most definitely a prima donna (see also this article), there was no trace of ego or of affectation of any kind. Her genuine, down-to-earth teaching style was as pure as the quality of her voice.

Copyright © 2012 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

PLEASE “LIKE” THE BLOG (ON THE RIGHT), & NOT JUST THIS PAGE

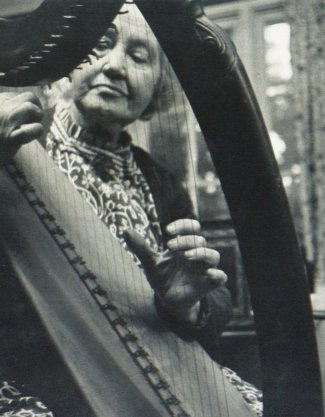

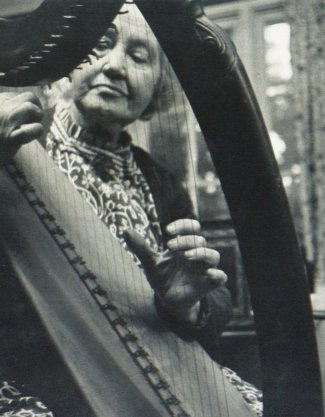

Mabel Dolmetsch, in later life I’d been meaning to buy Personal Recollections of Arnold Dolmetsch (published in 1957) for ages, and finally it arrived just after the recent conference in the Netherlands on Gustav Leonhardt (report from organizer, Jed Wentz, to follow), in which one of the speakers described Arnold as an amateur!

This is, of course, not at all true, even in the most literal sense.

Although the book hardly mentions money, we know that Arnold charged fees for his violin teaching and frequently for his performances, and sold the instruments he made.

His loss-making project to popularize triangular harpsichords for £25, which he announced without making any calculations, showed “the buoyant optimism which (come what may) supported Arnold through fair weather and foul”. The outbreak of war in 1914 halted the influx of orders, allowing Arnold to adjust the price for what was to become a “very popular and serviceable instrument”.

As for the slight disparagement with which the word ‘amateur’ is so often loaded, a contemporary reviewer of Personal Recollections described Arnold’s place in music history like this:

“He was the first modern musician to have an unqualified faith in early instrumental music, and to put this faith into practice by performing it on its original instruments and in its original form, instead of doctoring it up for modern consumption with patronizing “improvements” of scoring and presentation.”

The author, Mabel Dolmetsch (1874–1963), was Arnold’s third wife, 16 years his junior, who had started taking violin lessons from him in 1896 and, within a year, had become part of the concert-giving “family”, mostly performing on the violone or the viola da gamba. At the same time, she worked as Arnold’s instrument-building assistant, as she’d been learning wood-working, on the quiet.

The book is crammed with detail – about journeys and concerts and how the rooms looked; the costumes worn by the children (who, from an early age sang, played or danced); the variable quality of the catering; explanations of who was related to whom, and how which musicians came to play which instruments and why. It’s all rather rose-coloured, and not much is made of Arnold’s fiery temperament or his bankruptcy.

Famous people

The narrative is quite stiff with famous names, reminding the reader that Arnold was something of a superstar, having played the clavichord for President Roosevelt. He was a friend of many, including the antiquarian Fuller Maitland (co-editor of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book), Sir George Grove (of the Dictionary) and the pianist and composer Busoni (to whom Chickering – AD’s generous American employer – gifted a harpsichord).

His literary connections with W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and others are much less well known (to find out about them, see this blog). There’s also his involvement with the Arts and Crafts crowd (you know, the “green harpsichord” and all that), with Arnold playing the virginals to William Morris, as he lay dying.

Violin lessons

Arnold’s first violin teacher was a gypsy (really!), who disappeared one day, taking with him a violin borrowed from Arnold’s father’s music shop. Later, Arnold studied with the famous virtuoso Henri Vieuxtemps at the Brussels conservatoire and followed this by enrolling at the Royal College of Music, in its opening year of 1882, where his teachers included Sir Hubert Parry for harmony and Henry Holmes for violin. He then became a rather over-qualified part-time violin teacher at Dulwich College, the posh boarding school.

Searching for repertoire for his newly acquired “honey-toned” viola d’amore, in the Reading Room of the British Museum, Arnold stumbled upon stacks of 16th and 17th century English music for viols, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Instrument-making

Arnold learned the family trade of piano-making in his father’s workshop and was a skilled cabinet-maker by the age of fourteen, when he made a mahogany-veneered chest of drawers which Mabel described as “so faultless that not a thing has been altered from that day till this”. It’s amusing that Arnold had to be reminded that he had these skills, as he’d just been playing music for a period of ten years, and had quite forgotten (reportedly) that he knew how to restore instruments.

The whole story of the loss of the Bressan recorder, on Waterloo station, is given here in detail, and young Carl wasn’t as remiss as suggested elsewhere, but was rather overtaken by events. Arnold believed that this instrument was the only surviving playable recorder and set about making a copy, which ultimately brought about a huge revival.

Reviews from 1958

In one review, Mabel is criticized for “provided little insight into her husband’s methods of recreating a lost art through research, the reconstruction of ancient instruments, or the performances in which his labor culminated”.

Another, kinder reviewer – who obviously knew the family well, and later wrote Mabel’s obituary – wrote that this book “will give much pleasure to those who knew and loved [Arnold] well … and convey a little of the remarkable atmosphere in which he worked, to those who did not”.

She ends by saying, “Mabel’s loyalty and her serenity had more to do with [Arnold’s] success than this modest story tells.”

Also of interest:

The Dolmetsch Family with Diana Poulton: Pioneer Early Music Recordings, volume 1 (See blog post) Recordings, mostly from the 1930s, of Arnold, his third wife, Mabel, their children and musical friends playing small ensembles and viol and recorder consorts by the Lawes brothers, Purcell, Dowland, Marais, Leclair and others. This CD is not available in record shops, but you can order it here.

by Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

A page from William Byrd’s My Ladye Nevells Booke

This recording of the lovely Fifth Pavane, played by the English harpsichordist Colin Tilney, is one of the 42 compositions for virginals by William Byrd (c. 1540–1623) in My Ladye Nevells Booke of Virginal Music, one of the most beautiful Tudor manuscripts in existence. Continue reading My Ladye Nevells Booke: old news retold

Boris Ord and members of the King’s College Choir, taken in the Chapel at King’s, 1956

In an earlier post I introduced Boris Ord, the conductor of King’s College Choir for nearly 30 years. But what else do we know about him?

His biographical details – including active service in both wars – can easily be found online.

Briefly, he was an accomplished organist while still at school and studied at the Royal College of Music on a scholarship. In 1920 he went as organ scholar to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he founded the Cambridge University Madrigal Society, which toured abroad and so memorably sang madrigals during May Week on the river Cam from 1928. In 1923 he was elected to a fellowship at King’s College. Continue reading The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge and the man who made it famous. Part 2

Despite having amassed almost twenty thousand signatures on an internet-based petition, Sigiswald Kuijken’s baroque orchestra, La Petite Bande, has been definitively told that it will receive no more money from the Belgian government.

According to the committee which decided to pull the plug, the orchestra is no longer “innovative enough” and has outlived its usefulness, as there are now plenty of other similar groups! Continue reading Baroque orchestra, La Petite Bande, loses vital funding

|

Email subscription This feature is no longer available.

|