|

|

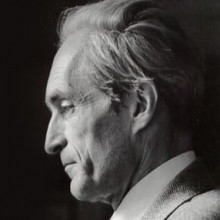

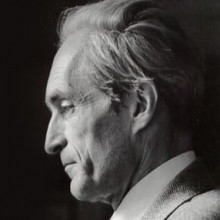

Alfred Deller was born on May 31, 1912 in the seaside town of Margate, in Kent, England and died on July 16, 1979 while on holiday in Bologna, Italy.

Alfred Deller can truly be called a pioneer of early music, developing his own voice and taking it to the public sphere in the face of frequent misunderstanding and even prejudice from his hearers. Considering the superstar status of Andreas Scholl and Philippe Jaroussky today, it’s odd that the clear, high-pitched voice of Alfred Deller was thought peculiar, even unnatural, during the early days of his career. Continue reading Alfred Deller, 100 years on, and what a lot has changed.

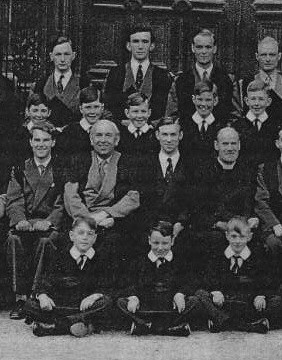

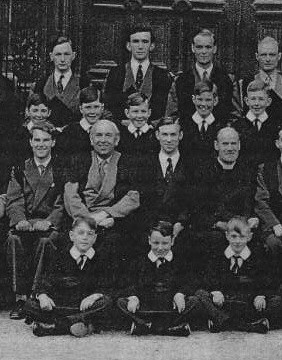

Part of an official photo of the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, taken c. 1950; Boris Ord is in the light suit with choral scholar Grayston Burgess on his right. You can just make out the top hats on the knees of the boys sitting on the ground.

When Boris Ord became director of Music at King’s College, Cambridge, in 1929, he took over a “fine choir” which had been developed by Dr A.H. Mann during his period of office, which had spanned 53 years! It’s not surprising, perhaps, that Dr Mann’s nickname was “Daddy”.

Although Mann had “a personality of great charm and kindliness [and] Boris had the highest respect for the achievements of his predecessor, he himself had a wider knowledge of music and a more comprehensive approach”. This is a quote from the slim postcard-sized commemorative booklet, written by composer Philip Radcliffe and privately printed for King’s College in 1962, the year after Ord’s death. Continue reading The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge and the man who made it famous. Part 1

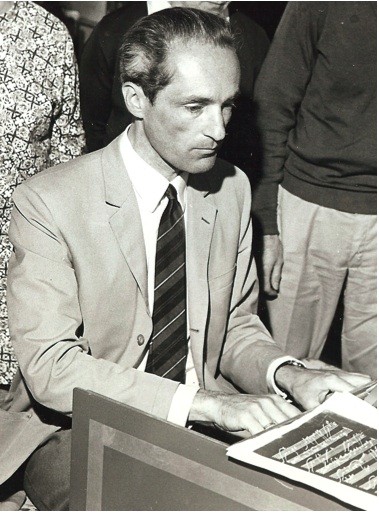

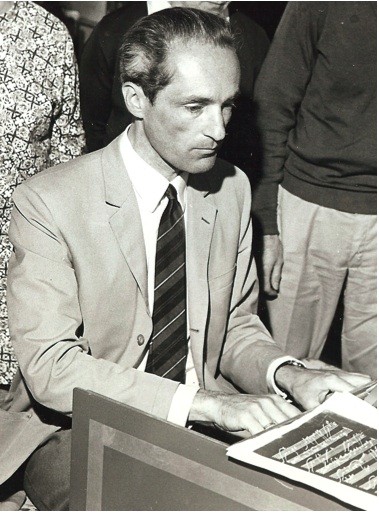

This is an extract from a 1971 interview, in which Frans Brüggen was asked to explain the “phenomenon Leonhardt”. At that stage, they had already been friends for more than 10 years and had become internationally famous through their records and for giving concerts together. Continue reading Frans Brüggen on Gustav Leonhardt

Mary Potts and Gustav Leonhardt © Estate of Mary Potts 2012 Following on from my last post on Mary Potts, the forgotten harpsichord teacher of many, including Christopher Hogwood and Colin Tilney (who, like Professor Peter Williams, went on to study with Gustav Leonhardt), I’ve been looking into who else, from Mary’s circle, is remembered – or not.

What’s clear is that being commemorated apparently has little to do with recordings made, concerts given or academic posts held. Many musicians who were very famous in their lifetimes have now disappeared almost without trace. Perhaps it’s more important to have tenacious musical executors who are determined to keep someone’s memory alive, or at least get some recognition for them. Continue reading In Early Music, how famous is “famous enough”?

Rarely, if ever, have so many letters of condolence and obituaries been written about a Dutch musician as for the recent death of the grand master of the harpsichord and icon of the early music movement. Gustav Leonhardt, the eminent teacher, and a very special person, is no more. On 16 January last, he died at his home in Amsterdam, at the age of 83. Continue reading “A Long and Beautiful Life”: A tribute to Gustav Leonhardt by Ton Koopman

Mary Potts and her beloved Shudi harpsichord in about 1950 © Estate of Mary Potts 2012 I didn’t really know that much about Mrs Mary Potts (1905 – 1982) when she was my harpsichord teacher in Cambridge, so I googled her name (in 2005) expecting to find a complete biography. She had, after all, been a student of Arnold Dolmetsch, in Haslemere, back in the 1920s, and had bought an eighteenth-century harpsichord by Burkat Shudi from him in 1929. Continue reading The forgotten harpsichord teacher of Christopher Hogwood & Colin Tilney

Gustav Leonhardt in 1972 It’s so sad that Gustav Leonhardt is no more.

I first heard him, partnered by Frans Brüggen in a concert in St Albans. Since then, I’ve seen him many times and, apart from the extraordinary playing, have often been struck by the fact that he mostly used his own elegant manuscript scores, presumably copied from ancient tomes during his early years in Vienna. Continue reading Gustav Leonhardt (1928–2012), the end of an era

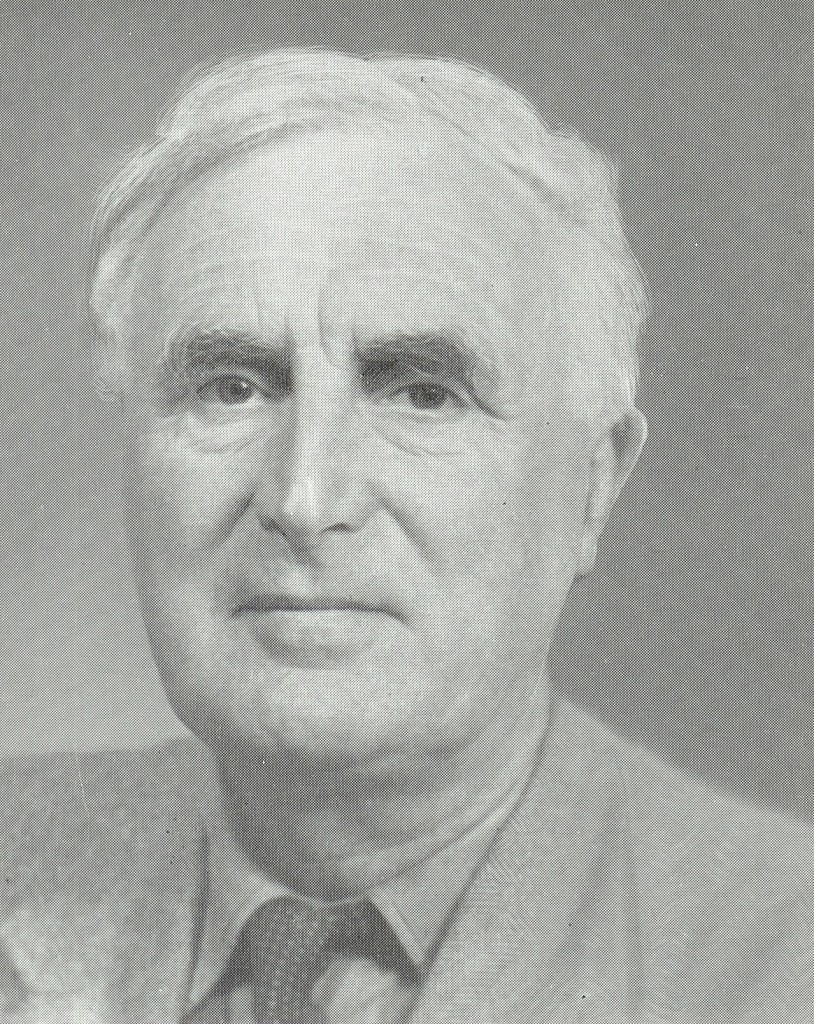

I mentioned in my post on Thurston Dart that I couldn’t find out much about Arnold Goldsbrough, who had been his teacher at the Royal College of Music 1938–9.

Since then I’ve tracked down Arnold’s son, now in his eighties, who has put me onto his dad’s surviving cronies and told me some stories. Through him, one way or another, I now have a great deal of previously unpublished material.

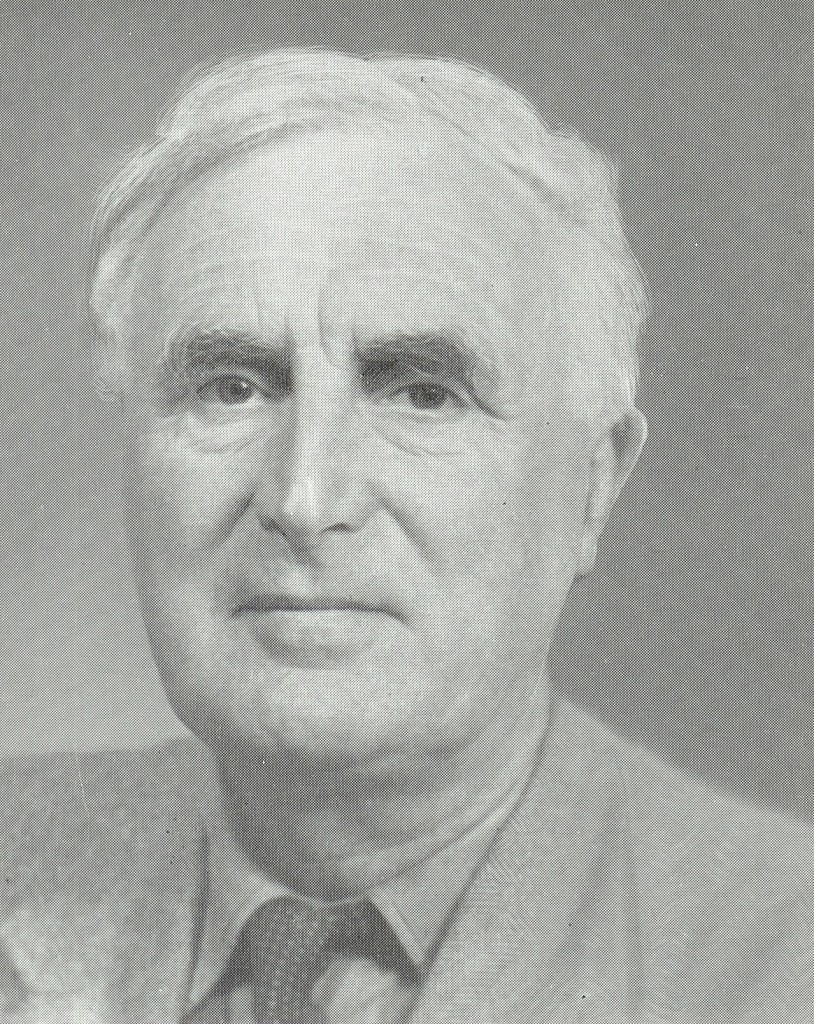

Arnold Wainwright Goldsbrough (1892–1964) – often misspelled Goldsborough – was an organist, harpsichordist, conductor, founder of what became the English Chamber Orchestra, and an early exponent of historical performance practice. Continue reading Arnold Goldsbrough – Yorkshireman, organist, harpsichordist & conductor Part 1

Surprisingly, it was Gustav Holst, the composer of The Planets, who conducted the first modern performance of Purcell’s Fairy Queen in 1911.

His longstanding friend and fellow composer Ralph Vaughan Williams introduced every number, and this lecture-concert was given by amateurs from London’s Morley College [for Working Men and Women], rather than some top-notch orchestra with a professional chorus and soloists.

Such was Purcell’s standing at the time.

I might never have known these startling facts had not a friend of a friend sung in Morley College’s centenary concert celebrating this event, which was given in September.

The Fairy Queen (see this whistle-stop tour) was first performed in 1692 at the Queen’s Theatre, Dorset Gardens, in London. It was a very lavish and costly production, and the Theatre Royal alone had put in £3,000. But, as the 1911 Daily Telegraph reviewer wryly commented, it turned out to be a succès d’estime – a popular success and a financial disaster.

Despite this, the managers of the Theatre Royal wanted to revive the production after Purcell’s death and, finding that the score had somehow been lost, they placed two advertisements in London newspapers in October 1701:

The Score of Musick for the Fairy Queen, set by the late Mr. Henry Purcel [sic] and belonging to the Patentees of the Theatre-Royal in Covent-Garden, London, being lost upon his Death, whosoever shall bring the said Score, or a true Copy thereof, to Mr. Zachary Baggs, Treasurer of the said Theatre, shall have twenty Guinea’s for the same.

There was apparently no response, for the work was never revived as a whole.

Fast forward to around 1900. The Purcell Society, which had started to publish its definitive scores in 1878, decided that The Fairy Queen was to be edited by the music critic J.S. (John South) Shedlock (1843–1919).

In the preface to his 1903 edition, Shedlock explained the work’s chequered past and his own thorough collation of various printed texts, along with the eight published and manuscript musical sources (included one owned by the King), which resulted in a very incomplete score. He wrote:

… the conjectural reconstruction of the score had been prepared and engraved, when, by a singular piece of good luck, there was found [by Shedlock himself] in the Library of the Royal Academy of Music a MS. volume which turned out to be none other than the long-lost score advertised for two hundred years ago.

Shedlock, of course, incorporated the rediscovered material (the ninth source) into his edition, which must have necessitated many new plates and repagination.

Inside the cover of the rediscovered score two names were written: “Savage” and “R.J.S. Stevens, Charterhouse, 1817”.

Shedlock deduced that the first name belonged to William Savage (c.1700–1789), a bass singer who had studied with J.C. Pepusch, a composer connected with the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, at the beginning of the eighteenth century and an enthusiastic collector of musical manuscripts. Savage probably obtained the score from Pepusch and then it passed on to Stevens, who had been educated in the choir at St Paul’s Cathedral, when Savage was Master of the Choristers there, from 1748 to 1773. It was Stevens (1757–1837), organist of the Temple Church and Professor of Music at Gresham College, who bequeathed the score to the Academy.

This is the second time that Stevens appears in this blog. The Amati violin owned by Edmund Fellowes previously belonged to him, and he had scratched his name on the back, from which we can gather that he was quite keen on labelling his possessions.

Shedlock organized a concert in which, according to the musical editor of Modern Society, he directed

a performance of selections from the work, given at St. George’s Hall on Saturday [15 July 1901]. Explanatory comments were aptly delivered by Mr. E. F. Jacques, and the “discoverer,” together with Mrs. Elodie Dolmetsch [second wife of Arnold Dolmetsch], presided at the harpsichord. (I must confess to being glad to live in the day of pianos.)

Lucy Broadwood (folk-song collector and great-granddaughter of John Broadwood, founder of the piano manufacturers), who was also present, wrote in her diary that “Evangi Florence and Mr O’Sullivan sang well … The Purcell Operatic Society was monstrously bad and the tenor also”.

But The Fairy Queen, which was re-published in 1903 in full score, remained unperformed, as a complete work, until Holst began his project, first announced in the Morley College Magazine in September 1910.

As there was no performing material, “a little army” of volunteer student copyists was enlisted. This mammoth task took several months and was complicated by the fact that many of the vocal parts had to be transposed, given the lack of countertenors and the untrained voices of the choir. The end result was 1,500 pages of manuscript; the names of all the scribes were mentioned in the programme.

The Old Vic

Sixteen weeks of rehearsals followed, and the first modern performance was given at the Old Vic on 10 June 1911, “before a highly musical but far from full house – [as] it is always easier to find performers than audiences at Morley …” (according to Denis Richards in Offspring of the Vic, 1958).

The critics were universally enthusiastic about both the quality of the performance and Purcell’s music, which was compared – rather oddly, I think – with works by contemporary composers:

… the instrumental music … shows Purcell’s wonderful originality of thought and boldness of harmonic progressions that has hardly been exceeded in the present day. (The Times)

Not even the most modern of our composers have achieved finer atmospheric effects than did Purcell in the wonderful song of Night, which occurs at the end of the second act … (The Daily Telegraph)

Despite the lack of male altos, one song, “One charming night” (Secrecy’s Air in Act II), was sung at the original pitch, according to The Times, “by Mr. Ernest Raggett, a high tenor with remarkable easy production”.

This expedition into early music wasn’t a one-off for Holst, who was Music Director of Morley College from 1907 to 1924 and gave his services for free. Holst insisted in providing a rigorous diet of “proper” classical music and “firmly declined to pander to the then existing taste”, according to an interview given in 1921.

During his time there, he programmed Bach’s Magnificat, Handel’s Acis and Galatea, some Haydn and Mozart symphonies (unusual at the time), Dido and Aeneas and the Incidental Music to Purcell’s Dioclesian, which was another first modern performance.

Together with Vaughan Williams, with whom he’d been friends since their time as students at the Royal College of Music, he successfully staged performances at Morley College of extracts from Purcell’s King Arthur, Bach’s Christmas Oratorio and Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice.

They both shared a keen interest in Purcell (RVW even edited a volume of Welcome Odes), madrigals and the Tudor composers, no doubt helped along by Edmund Fellowes’ enthusiasm and active promotion of his own work. Holst and Fellowes did meet at least once.

These influences certainly affected Vaughan Williams’ composing style more obviously than Holst’s, perhaps as a result of his work on The English Hymnal. In any event, John Alexander Fuller Maitland music critic and co-editor of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book observed that in Vaughan Williams “one is never quite sure whether one is listening to something very old or very new”.

Thanks are due to Elaine Andrews and Edward Breen at Morley College and to the library staff of the Royal Academy of Music.

by Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

I was a schoolgirl in Sydney when I first heard a recording of The Play of Daniel. I’d never heard anything like it. I was completely blown away. I learned passages off by heart and chanted them to myself on walks in the bush. I bored my friends to death with Daniel. I can’t remember who, if anyone, introduced me to it; I probably just picked it up in a record shop out of curiosity.

I certainly didn’t know then that I was listening to an historic recording, the 1958 LP that put the New York Pro Musica Antiqua and its director, Noah Greenberg, on the map and triggered in many people a lifelong fascination with early music.

Half a century on, listening to the recording on remastered CD, I’m still impressed with its vitality and joyful force. Bloodless and academic this is not.

So what was this extraordinary work? The Play of Daniel (in Latin, Ludus Danielis) has been called a medieval opera – and it certainly has plot, character, spectacle and emotional power. It is also described as a liturgical drama, but it contains some secular elements that differentiate it from other church music dramas of the time.

It was devised in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, possibly under a single overall director, by students and junior clerics of the cathedral school in the French town of Beauvais, and comes down to us in a manuscript of c. 1230 now in the British Library (Egerton MS 2615).

Evidence from the manuscript connects the play with the liturgy for the Feast of the Circumcision on 1 January, and it could have been presented as either a complement or a corrective to the secular celebrations of the Feast of Fools on the same day, for it dramatizes the Church’s message that the mighty will be toppled and pagans defeated.

The play retells the Old Testament story of the prophet Daniel, in two ‘acts’: first, Daniel interprets the mysterious writing on the wall foretelling the collapse of Belshazzar’s kingdom; this is followed by the episode of the lions’ den, rounded off with Daniel’s prophecy of the birth of Christ.

There’s a big cast of characters: a narrator, Daniel, the two kings, a queen, wise men, envious counsellors, the prophet Habakkuk, and sundry advisors, satraps, courtiers and angels – even two lions. The manuscript contains only the text, in Latin and medieval French, some stage directions, and a single line of music – a spare but suggestive melodic core around which a great variety of elaborations have been woven, sometimes controversially, into modern performance.

An unlikely smash hit is born

The man responsible for bringing this forgotten work to vibrant life in the twentieth century was Noah Greenberg (1919–1966), a working-class Jewish socialist from the Bronx, largely self-taught in music, and the most audacious and charismatic of the American early music pioneers. In 1953 he happened upon the Play of Daniel in an article by William Smoldon, an expert on liturgical drama who had transcribed the British Library manuscript in the 1940s. Greenberg had already successfully launched the largely semi-professional New York Pro Musica Antiqua (brief history and a full discography here) in 1952, and he resolved to stage Daniel for the first time for modern audiences.

Five years of planning, discussion, editing, locating “authentic” instruments, stage and costume design, and fundraising later, the first modern performance of Greenberg’s performing score, based on a new transcription by Rembert Weakland and with English narrative interpolations by the poet W.H. Auden, was given at the Cloisters of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in January 1958.

I haven’t found any online video or audio clips of that first performance, but here are two excerpts from a 50th-anniversary production filmed in 2008 at the Cloisters, which updated various features such as pronunciation but stayed close to the spirit of ’58:

Belshazzar’s Feast

Daniel reads the writing on the wall

Greenberg’s instrumental scoring was largely speculative and was eventually criticized even by his collaborators; but, of course, it was the exotic, thrilling sounds of the straight trumpet, rebec, psaltery, harp, drums and portative organ that captivated audiences. And captivated they were: every performance sold out and rave reviews bristled with superlatives.

Garbed in glowing colors

The production, with its cast “garbed in glowing colors, as if they had stepped out of the illuminated pages of a medieval manuscript” (Edward Downes, New York Times, 3 January 1958), was a media sensation as well as a public triumph. The voices of the high tenor Russell Oberlin and the tenor Charles Bressler, who portrayed Daniel, were particularly praised.

Far from being a flash-in-the-pan revival, Daniel became central to the New York Pro Musica’s repertoire, and toured the USA and Europe. It was recorded soon after the first performance, and that recording has recently been enshrined in the US National Recording Registry as a hallmark of early music performance. A televised version was shown in the USA every Christmas from 1958 for the next decade.

Although many others have since performed and recorded this work, Greenberg’s Play of Daniel is so significant because it was the first modern performance of a complete medieval liturgical drama, and because it marked such a radical departure from the drily academic treatment that was then the norm for the performance of medieval music.

Greenberg’s interpretation wowed thousands who had never experienced medieval music – or possibly even classical music – before.

But its success also depended on the surge in music-recording technology, and in particular the development of the LP, in the 1940s and 50s. Daniel was a landmark not only in the study and interpretation of medieval music but also in cultural packaging: the performances, the recording (including a booklet with scholarly notes, not at all common in the 1950s), and the performing edition made up an integrated project that doubtless saturated the music media for a while.

Yet, though the New York Pro Musica became increasingly professionalized after Daniel, they arguably never quite captured the public imagination again as they had done in 1958. Their later projects seem, to me at least, like sequels.

© Mandy Macdonald 2011

Do you agree? And does anyone have any photos or that TV film? [Please comment]

|

Email subscription This feature is no longer available.

|