|

|

For me, two stories from Fellowes’ 1946 autobiography, Memoirs of an Amateur Musician, stand out:

Byrd’s Great Service

According to Fellowes, “the greatest thrill in the course of the whole of [his] researches” was finding Byrd’s Great Service, which he stumbled upon while visiting Durham to complete some Gibbons anthems. As soon as he started transcribing the folio part-books he recognized that he had found “a major work whose existence was till that moment unsuspected”. It has subsequently been described as “the most elaborate and the lengthiest setting of these standard liturgical texts ever written for the Anglican Church”.

But, after making the find, “a keen disappointment followed” as he discovered that he only had eight of the ten necessary parts. Further investigations revealed another, smaller part-book and, as he went to get it, he wrote:

My feelings may be imagined, for it depended on this whether or not it was going to be possible to produce a satisfactory score … My luck was in!

He later found some fragments of the tenth part in the British Museum and reconstructed the rest for the published score.

Here’s a recording of part of the Great Service made by Fellowes and the St George’s Singers in January 1923, followed by one from the Tallis Scholars from a much more recent date.

Yes, I know the pieces don’t match …

William Byrd – Nunc Dimittis: Gloria from the Great Service ed. E.H. Fellowes, with the English Singers

William Byrd – Te Deum from the Great Service, with the Tallis Scholars

Dolmetsch and Galpin

Fellowes was so irritated by Arnold Dolmetsch’s demand for a twenty-guinea fee for playing an obbligato lute part of only 18 bars in a planned performance of Bach’s St John Passion, in 1913, that he “let the matter drop”, borrowed a lute from fellow clergyman F.W. Galpin, taught himself how to play it, and performed in the concert – for free. He later ended up owning that instrument, when Galpin (after whom the Galpin Society is named) sold his collection a few years later.

Galpin’s collection, which consisted of almost 600 items and had taken him a lifetime to find, was bought by a benefactor for the Boston Museum in the United States.

I wonder whether such a sale would be allowed today, or if someone would step in and insist that it was bought for the nation, as it contained a goodly part of our (British) heritage. Given “dumbing down” and what’s happened with the musical instrument collection at the V & A (see also this Facebook group), perhaps no one would even bat an eyelid.

To end with, a madrigal double bill, sung by the St George’s Singers conducted by Rev. Dr E.H. Fellowes, as part of The Columbia History of Music by Ear and Eye.

Orlando Gibbons – The Silver Swan; John Farmer – Fair Phyllis

Your Part:

Unfortunately, I’ve not been able to find any recordings of Fellowes’ solo violin playing or of him lecturing or singing a lute song to his own accompaniment, all of which would be quite important historical documents!

I also don’t know what happened to his priceless old Italian violin or that lute.

Can anyone help with any of this?

Or, as ever, does anyone have reminiscences or anything else to add? [Please comment]

Edmund aged 7

Fellowes’ life and legacy

Aided in the churchy sphere by Professor Sir Percy Buck, who was one of his oldest friends (and a teacher of Mary Potts at the RCM), Edmund Fellowes brought about a revolution, albeit a gentle one: he both changed the way in which choral and other early music was understood and raised the quality of performance exponentially within his own lifetime. Fellowes was a scholar–performer before we knew the word.

Despite the fact that his name often appears in footnotes, and there is an entry for him in Grove, his contribution to the revival of old English music and performance practice hasn’t been much appreciated since Sylvia Townsend Warner wrote about his tenacious detective-work, describing him as “inexhaustible and obstinately conscientious”, in an article that was printed alongside his obituary.

Sixty years after his death, pretty much all we know about him comes from his autobiography published in 1946.

A charmed childhood

In his book, modestly called Memoirs of an Amateur Musician, Fellowes gives an amazingly detailed account of his very well-to-do and cultured background, which involved staging French plays at home and going to concerts given by people like Rubenstein, Liszt and Clara Schumann.

His mother was one of the best amateur players of the time. She had been taught piano by Julius Benedict and singing by Manuel García, founder of the famous García School of Singing, and sometime teacher of his famous sisters: Pauline Viardot-García and Maria Malibran (who was recently celebrated by Cecilia Bartoli).

Fellowes had piano lessons, with his mother, from the age of five, and began the violin at six, getting three lessons a week; so he made good progress before going to school, which didn’t happen, apparently, till he was nine. By his own reckoning, he was not yet seven and a half when he met and played for the famous violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim, who offered to take the young Edmund as a private student in Berlin. This great opportunity was declined “so that I might not leave the conventional lines of a English boy’s education”.

Here’s Joachim playing Bach’s Adagio in G minor, in 1904.

The Amati violin

Around the same time, the 1679 “Stevens” Amati violin (which had belonged to R.J.S. Stevens, glee-writer and organist of Charterhouse) was bought for him by the husband of a cousin, for £100, “so that he would have a really good violin to play on when he grows up”. And he certainly put it to good use, playing chamber music throughout his life in public with professionals, starting at the age of 13.

Sadly, I’ve been unable to find any solo recordings of Fellowes playing the violin. But here he is in a string sextet, consisting of 2 violins, 2 violas and 2 cellos – which was the best approximation that they could make for a chest of viols – in 1923, Byrd’s tercentenary year. This is another sound file from CHARM.

William Byrd – Fantazia for String Sextet or small String Orchestra [from Psalms, Songs and Sonnets, no. 11, part 1], edited by E. H. Fellowes

Later life

Predictably, he went to Oxford, was ordained as a priest in 1894, and received his MA and B.Mus. degrees in 1896. After a stint as Precentor at Bristol Cathedral, he spent the rest of his life, from 1900 to his death in 1951, as a minor canon of St George’s Chapel, Windsor, “which allowed him the necessary leisure to pursue his interests in music, cricket [he published A History of Winchester Cricket in 1930] and genealogy”. See details of his spartan living conditions here.

He married Lilian Louisa Vesey Hamilton, the daughter of an admiral, in 1899.

To end with, here’s a lively madrigal recorded around 1930. Fellowes is conducting the St George’s Singers, about whom I know absolutely nothing.

Thomas Morley – Sing we and chant it

Next week: Fellowes’ greatest discovery and how irritation caused by Arnold Dolmetsch forced him to learn the lute.

Any comments so far? And does anyone have reminiscences or anything else to add? [Please comment]

Fellowes’ interpretation of Tudor music

As a church musician himself, Fellowes recognized that what little Cathedral repertoire there was in his day was usually poorly performed. “The interpretation of Tudor music began to force itself on my attention,” he wrote. “It became increasingly clear that rhythmic irregularity, as an essential feature of this music, was being generally unrecognized and ignored.” Apart from that, old music was sung much too slowly, and often, in church music, at the wrong pitch. Everything, even sprightly madrigals like Morley’s “Now is the month of maying”, sounded like a dirge.

Fellowes was also an educator who believed in leading by example. He wrote in 1946:

… some representative compositions of Byrd were produced in connection with the William Byrd [c. 1540–1623] tercentenary in 1923. The record of Byrd’s ‘Short’ Magnificat was a revelation in its beauty when rightly performed; it exerted a widespread influence in church-music circles.

And here is that very record, courtesy of the CHARM project, which has digitalised almost 5000 historic recordings from 78 rpm discs and made them available for free download.

William Byrd – Magnificat (Short Service), ed. E.H. Fellowes, with the English Singers (Flora Mann, Winifred Whelen, Lillian Berger, Steuart Wilson, Clive Carey and Cuthbert Kelly) recorded 29 January 1923.

His editions

Morley’s four volumes of madrigals had, in fact, been Fellowes’ first editing project, which he completed in the summer of 1912. His edition included irregular barring – then a radical novelty. Unable to find a publisher willing to take the risk, Fellowes made an appeal for subscribers and, within a year, almost 400 people from Washington DC to Vienna had signed up. On the list were such illustrious names as Sir Edward Elgar, Lord Gladstone (the former prime minister), Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Sir Henry Wood, Alfred Einstein (the German-American expert on the Italian madrigal), Bohemian-Austrian musicology pioneer Guido Adler, O.G. Sonneck of the Library of Congress (who bought a clavichord from Arnold Dolmetsch) and Alfred Wotquenne (cataloguer of Gluck and C.P.E Bach).

Recordings, concerts and lectures

As well as transcribing manuscripts and early editions for publication, Fellowes made it his business to actively promote the music he edited by conducting and giving lecture-recitals, often using his own gramophone records for the illustrations or demonstrating on the lute.

Another quote from his autobiography:

It was in the autumn of 1921 that I entered into negotiations with the Gramophone Company (His Master’s Voice) to make some records of madrigals. It was obviously a good way of demonstrating in a wide field the proper method of interpreting this music …

The Company preferred that their ‘stock singers’ should do the work as being familiar with recording requirements. In the end it was agreed that I should employ the English Singers with the proviso that they should receive no fee unless the Company was satisfied with the result. These records, made in the factory at Hayes in extremely primitive conditions under my direction, were remarkably good. They were followed by many more …

The English Singers

Fellowes’ editions were further popularized by live performances of the English Singers, a one-to-a-part group trained by him.

He describes the first appearance of the English Singers, at the Aeolian Hall in February 1920, as

the first occasion upon which in modern times madrigals were properly interpreted on a concert platform … The audience was entranced. Here was something quite new to an English audience, and they rose to it.

When, in 1922, the English Singers gave a concert in Berlin, the German critics naturally assumed that their lively style of interpreting English madrigals was “the fruit of centuries of carefully preserved tradition”. Writing as critic of the Nation and the Athenaeum, the musicologist E.J. Dent put right this misconception:

Their style is the fruit not of tradition, but of scholarship, of historical erudition, by Dr Fellowes, and the common sense supplied by themselves.

One of the singers in this group was Clive Carey, who taught Joan Sutherland (yes, really, La Stupenda), and his correspondence with Professor Dent, resulted in a book that will figure in later posts.

Here’s a recording, made in the same year (almost 90 years ago!), of Thomas Bateson’s “Cupid in a bed of roses” edited by Fellowes, who may or may not have been directing the group. Apparently, they went on to achieve “phenomenal success”, particularly in the USA.

Finally, a rather quirky recording, complete with spoken announcements, which I just found online. It combines (from both sides of a very small 78 rpm disc) a folk-song arrangement, “Just as the tide was flowing”, by Ralph Vaughan Williams, with the madrigal “In going to my naked bed”, by Richard Edwards. The madrigal text is spoken from 2.18 and music starts at 3.20.

Next week: Fellowes’ extraordinary background, an Amati violin and a meeting (aged just 7 years old) with the Hungarian virtuoso, Joseph Joachim

Any comments so far? And does anyone have reminiscences or anything else to add? [Please comment]

Reproduced by kind permission of the Dean and Canons of Windsor

Edmund (E.H.) Fellowes (1870–1951) – pictured here with his wife – was made a Companion of Honour in 1944. Always a meticulous man, he compiled an annotated alphabetical list of all the 220 letters of congratulations he received. It includes almost every well-known contemporary British musician and composer, along with many famous names from other fields, which demonstrates his reputation at the time.

He’d already had been given an MVO in 1930, as well as honorary doctorates from Oxford, Cambridge and Trinity College, Dublin. He had conducted a “fantastically successful” nine-week concert tour of Canada, with a choir made up of “the Gentlemen of His Majesty’s Free Chapel of St. George in Windsor Castle and the Choristers of Westminster Abbey” and had returned to make five further three-month-long North American lecture-recital tours (the first at the invitation of President Coolidge’s wife) which ended, in 1936, with his final lute song performance (at the age of 66) being broadcast on the radio from New York. He also toured Holland and Belgium with his lute, and was a very popular public speaker, who had been filling halls throughout the UK since 1904.

Although once rather unkindly described as “a stiff-necked Anglican clergyman,” he was also quite a celebrity. A more sympathetic musical portrait of him comes from his younger contemporary Herbert Howells (1892–1983), who characterized him in the second movement – entitled “Fellowes’s Delight” – of his set of piano miniatures Lambert’s Clavichord, published in 1928.

Research

Through his researches in libraries, largely at the British Museum and the Bodleian in Oxford, Fellowes rediscovered the lute song, disinterring John Dowland and a host of forgotten English composers in the process, and single-handedly edited the whole repertoire of 450 songs, thereby saving it from oblivion.

Here are two jewels that may have not made it, had it not been for Fellowes.

Alfred Deller with Desmond Dupré, Philip Rosseter – ‘What then is love but mourning’

Andreas Scholl with Andreas Martin, John Dowland – ‘Flow my tears’

‘Flow my tears’ is now probably the most famous lute song ever. And Fellowes’ editions must have made these songs easily available to composer Benjamin Britten, who used ‘Come, heavy sleep’ and ‘If my complaints’ respectively as bases for sets of variations for guitar (Nocturnal, 1963) and viola and piano (Lachrymae, 1950). Stephen Goss (in this pdf) says that Britten drew his text of ‘Come, heavy sleep’ for Nocturnal from Fellowes’ 1920 edition of Dowland’s First Booke of Songs or Ayres.

Fellowes also edited 36 volumes of madrigals, published as The English Madrigal School (later revised by Thurston Dart) and twenty volumes of music by William Byrd. He was one of the four editors (with Alexander Ramsbotham, musicologist-turned-author Sylvia Townsend Warner and her former teacher and married lover, Sir Percy Buck) of the Carnegie Trust’s 10-volume series: Tudor Church Music, which contained works by 24 composers including Thomas Tallis, Orlando Gibbons, Robert White and Hugh Aston.

Writing

Among Fellowes’ books are The English Madrigal School, English Madrigal Verse (1588–1632) and biographies of William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons. Although superseded by modern scholarship, these books were ground-breaking at the time. His study of Anglican Church music, English Cathedral Music from Edward VI to Edward VII, is still the standard work, apparently. He also contributed more than 50 articles to the third edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

Quite a lot, really.

Here’s a quote from Fellowes’ autobiography, followed by a recording of the group he mentions:

Some more good records were made under my conductorship for the Columbia Company by a group called the St George’s (Bloomsbury) Singers [Fellowes’ parentheses are to differentiate this group from his own St George’s Chapel Choir, at Windsor Castle]. This was after electric recording had been introduced… with all the advantages of modern devices…

This note on electrification underlines the fact that this record was made more than eighty years ago.

Sumer is i-cumin in [c. 1930 as part of The Columbia History of Music by Ear and Eye]

I was quite entranced by this piece, when I first heard it as a boy. It was part of a huge stack of 78 rpm records that I found in a cupboard at school. I was given permission to take them home, as 78s had long been obsolete and they were going to be thrown away. See here for more details about this ancient round.

More about Fellowes’ editing and conducting next week, with recordings made in the 1920s.

Any comments so far? And does anyone have reminiscences or anything else to add? [Please comment]

I knew the name Virgil Fox, as one half of the dynamic duo who – with English émigré E. Power Biggs – had established the organ as a concert instrument in the US, rather than simply being the box of tricks which accompanied hymns in church. But until now, I had never heard him play.

It was, then, with great curiosity and a more or less ‘innocent ear’ that I listened to an all-Bach LP that I’d bought recently in Newcastle upon Tyne (UK). There was a picture of an elaborate and highly gilded organ case on the record sleeve, so, although no organ was specified, I was hoping for the best.

The first thing that struck me about his playing was the extent of the rubato. Apart from all the pushing and pulling, Fox’s interpretation consisted largely of ultra-romantic, highly skilful and ever-changing registration. I had no sense that I was listening to an historically informed performance, and certainly it was not played on an old organ, as there was much judicious use of what sounded like, several swell pedals. And, apart from the trills marked in the scores, there was no added ornamentation or ‘filling in’ as, say, Ton Koopman would do.

And this use of the swell pedal was not just limited to the large Preludes and Fugues on this disc, but also applied to the slow movement of a Trio Sonata! Running through a veritable kaleidoscope of tonal possibilities (as if Mr Heinz wanted to show off all his 57 flavours in just one sitting), Fox swelled up and down, drawing us in to an mysterious inner world of colour and harmonies, which wouldn’t have seemed out of place in a piece by César Franck or Tournemire.

All the notes were still there, and (unlike Eric Morecambe’s famous TV rendition of Grieg’s Piano Concerto, with André Previn) they were in the right order, but the overall effect was something quite new to me. Odd.

It was all strangely engaging and made excellent background music for doing the dishes! But then, I had to go back and listen again and really take in what he was doing – which was with consummate skill and a 100% certified copper-bottomed technique. It was exciting playing, but not without the odd slip (no doubt to confirm that these pieces weren’t being played, at high speed, by a machine)!

I had no idea, however, the extent to which he had been a superstar, and toured with a four or five manual electronic organ to packed sports stadiums all across the US. He even had a sophisticated light-show, which involved a ton and a half of equipment. We are talking pre-1980, remember.

I didn’t know, either, that he was a student of Marcel Dupré, or that he was a friend of French composer Maurice Duruflé, so he certainly knew how to play that repertoire. And, as if to confirm that: one of his great successes both then in concerts and now, in terms of current ‘views’, is a glittering piece by the Belgian organist, Joseph Jongen.

There’s a comprehensive wiki and a book and several articles, so Fox is far from being forgotten.

There are also plenty of videos online, showing him being interviewed and in exuberant full flight, particularly in Bach’s ‘Gigue’ fugue, which he always finishes off with a music-hall-esque ‘dum-doo-doo dum-dum… do-dum’.

As a comparison, here’s E. Power Biggs playing the same piece, in a not dissimilar way, on the famous 1958 Flentrop ‘tracker’ organ at Harvard, but without either dancing or clapping.

Although Fox decried all purists as ‘creeps’, he was a very effective one-of-a-kind musical zealot and a worthy early music pioneer who, particularly through his famous ‘Heavy Organ’ all-Bach stadium concerts, brought baroque music to a very large and, one suspects, mostly stoned young audience.

See this article about Fox and Power Biggs, which recognizes the very different means that they both used to create new audiences for the organ.

With the death of Dart’s close personal friend and executor William Oxenbury, Gustav Leonhardt is now probably the only person alive who knew Dart, but not as a teacher. They were apparently well acquainted and served together on the jury at the harpsichord competition at Bruges.

Their approach to Froberger seems quite similar in these recordings of his Lamentation for Ferdinand III, made within a year of each other, in which Dart uses Leonhardt’s favourite instrument: the clavichord. See a review of Dart’s recording here:

Thurston Dart 1961

Gustav Leonhardt 1962

Choice of instruments

Otherwise, their choice of instruments was quite different. Although Dart sometimes used historical instruments, some of which he restored himself, he apparently preferred modern steel-framed “revival” harpsichords.

From 1951 Dart was involved in the annual quadruple-harpsichord jamborees at the Royal Festival Hall with George Malcolm, Eileen Joyce and Denis Vaughan (who was instrumental in the creation of the UK National Lottery) – all playing “whispering giants’” which needed to be amplified to balance with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The conductor was Boris Ord, another unsung early music pioneer.

Who knows anything about Boris Ord or has solo harpsichord or organ recordings featuring him? [Please comment]

On the appearance in July 1957 of a recording, the Gramophone reviewer enthused as follows:

Those who have enjoyed, year after year, the unique Festival Hall concerts at which Mr. Thomas Goff assembles a resplendent quartet of his inimitable harpsichords, will rejoice that some part of this hardy annual repertoire is at last made available on disc.

Here’s the beginning of Bach’s Concerto for three harpsichords in C major.

Dart continued to play modern-style harpsichords, with pedals and a 16-foot register, up to his last recording, made with Igor Kipnis and issued posthumously in 1972. Here they are in Couperin’s Allemande a deux clavecins (IXe Ordre), in which Dart’s Goff was parried by a Goble of equally gargantuan proportions.

Dart did leave us a recording of some historical organs, however. The 1958 sleeve notes for Two Centuries of English Organ Music state:

This record contains, it is believed for the first time in the history of the gramophone, a survey of English Organ Music (sic) stretching over 200 years, played on instruments contemporary with the examples selected. No pipework is used that was not part of the original organ…

I can only imagine that some tracks sounded very out of tune, at the time.

Here’s For a Double Organ from Melothesia by Matthew Locke, played on the Renatus Harris organ at St John’s Church, Wolverhampton

Dart’s career

Given his background, it seemed unlikely that Dart would end up as a professor of music, first briefly at Cambridge and then at King’s College, London. He sang a solo, as a boy soprano, on the BBC when he was a Chapel Royal chorister and, from 1938, spent a year at the Royal College of Music on “keyboard instruments” with Arnold Goldsbrough, about whom we also know precious little today.

Does anyone know anything about Arnold Goldsbrough or have memorabilia, photos, or recordings – particularly of his organ or solo harpsichord playing? [Please comment]

Dart then took a Maths degree, and after war service – during which he met Neville Marriner, when they were both patients in a military hospital – continued his musicological studies privately in Brussels, with the erudite and very aged Charles van den Borren (born in 1874), whom he outlived by only five years!

Mary Potts told me that he had said that he knew he would die young, and consequently needed to be very productive. And, indeed, aged 49, he died of stomach cancer; midway through a recording of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, with the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. Sir Neville Marriner reports his demise in the booklet which accompanied the set (see also his extensive personal tribute):

We recorded Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 on January 30, 1971. Bob [Robert Thurston Dart] looked grey and tired. On Monday he did not make the frequent journeys with us to the control room. On Tuesday he had a mattress by the harpsichord so that he could rest between ‘takes’. He played the continuo for the first movements of Concertos 2 and 4, and for the serene Adagio [from a Sonata in G, BWV 1021] used for the slow movement for No. 3. I put him into the car which took him to the clinic at 5.30 P.M. and saw him no more.

His place in the 5th Brandenburg was taken by George Malcolm and the remaining continuo was split between Raymond Leppard and Colin Tilney (a student of Mary Potts). Although Dart had already recorded this concerto with the Philomusica – complete with a registered crescendo in the first movement cadenza! – it would have been interesting to see how his views had changed, more than 10 years later.

No published biography

Although dedicated students organized a reunion, in 2001, to commemorate the 30th anniversary of his death; there are no plans currently to write a book about Robert Thurston Dart, as the prime candidate for that job has also died. However, since I started writing these posts, Greg Holt has assembled an online biography from items of “Dartiana” which he inherited, which includes some very interesting details and early photos.

One final claim to fame

Reportedly, it was the crumhorn hanging on Dart’s study wall – which formed part of a tantalizing, now dissipated and largely undocumented instrument collection – that inspired David Munrow to explore early wind instruments, and ultimately led to the formation of the Early Music Consort of London.

Who has lecture tapes, private recordings, personal recollections or anything else to add? [Please comment]

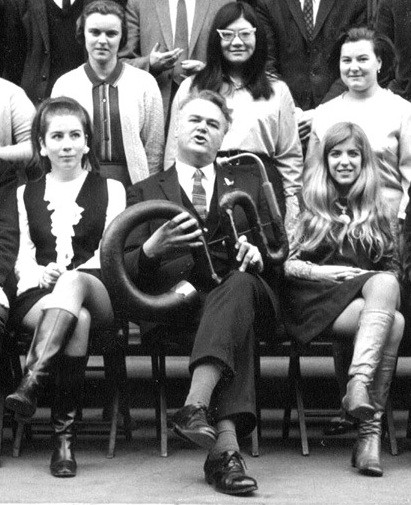

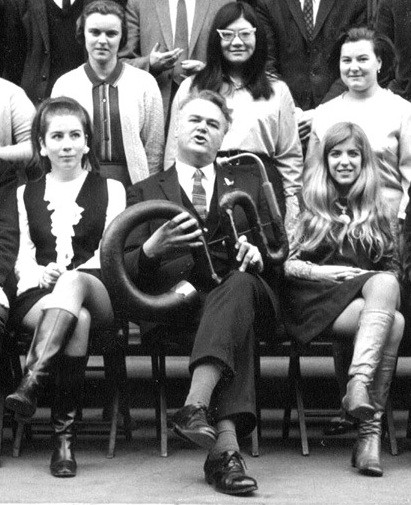

Music Faculty, King’s College, University of London, 1968. Reproduced by kind permission of King’s College London. Professor Thurston Dart (holding the serpent) was at the time King Edward Professor of Music and established the faculty in 1964. The composer Michael Nyman well-known for his collaboration on Peter Greenaway’s films, is described on a movies website as being mentored as a PhD student by the “famed” Baroque scholar, Thurston Dart, at King’s College, London; but I wonder how famous Dart actually was then – and now, 40 years after his death. If the current CD catalogue is any indication, then “not very” is the answer.

From the 76 records Dart made, only two clavichord compilations (consisting largely of works by Froberger and Bach’s French Suites) are currently available, along with some English organ music, plus a little continuo tinkling for Anthony Lewis and, oddly, Klemperer with Schwarzkopf. His harpsichord recordings, and his work with the Philomusica, the re-named Boyd Neel Orchestra, which he took over until 1959, are all long gone.

Here’s Dart playing C.P.E. Bach’s Concerto in F Major Op. 7, No. 2 (W.C56) on an eighteenth century chamber organ with the Boyd Neel Orchestra on an

LP from 1956.

Dart made many recordings for the L’Oiseau-Lyre label including Bach’s Orchestral Suites, the Triple Concerto, the Harpsichord Concertos, as well as Dowland’s Lachrymae, Handel’s Water Music, Couperin’s Pièces de violes and Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie. There was also lots of Purcell: one of his earliest recordings (on the French label BAM, made in 1956) was a disc of Purcell’s Trio Sonatas (1683) with him as leader of the Jacobean Ensemble, with Desmond Dupré on the gamba and violinists Neville Marriner and Peter Gibbs. Here’s the Gramophone review of this LP and a short extract.

Purcell – Trio Sonata No.1

TD NM PG DD

Does anyone know anything about Desmond Dupré? [Please comment below]

The dozens of lectures which Dart broadcast for the BBC have also all but disappeared, except in the memories of those who heard them. I have, though, been able to track down the first few chapters of his book on John Bull to a former student, Greg Holt, and a single recording, also on Bull, held by The British Library. Although there is now a Thurston Dart Professor at King’s College London, the books he bequeathed to their library can no longer be identified as ever having been his.

A memorial volume edited by Ian Bent, Source Materials and the Interpretation of Music (London, 1981), was published 10 years after Dart’s death. The six-page biographical sketch included there is almost all that is left of him, otherwise we have only Greg Holt’s recent biography (see next post), a couple of wikis, an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography and some obituaries.

His most lasting legacy would seem to be the three generations of musicologists he trained when he was at Cambridge and KCL. They include such famous names as Christopher Hogwood; the Bach and organ expert Peter Williams; Sir John Eliot Gardiner, who has recently called him “the Sherlock Holmes of musicology at the time”; the harpsichordist Davitt Moroney and Nigel Fortune, co-author of the Monteverdi Companion and long-term Grove editor. Nigel told me that Dart had the knack of getting his students to transcribe lute tablature and other early notation, so that he could judge if they were worth considering further.

Dart wrote only one book, the slim but seminal The Interpretation of Music (London, 1954) which, according to Harry Haskell in The Early Music Revival: A History, “heralded the new philosophy of historical performance that transformed the early music movement in the post-war period”.

His output, though, was prodigious in terms of the huge amount of completely unknown music that he edited (as well as revising earlier work by E. H. Fellowes) and the many articles he wrote in scholarly journals and elsewhere, not yet, apparently, all accounted for. I’m told that he was a charismatic speaker and inspired teacher.

Allen Percival, one of Dart’s students at Cambridge in the fifties, wrote:

Soon [Dart] had us playing Landini in what were then unheard-of realizations, singing nasal medieval songs, attempting to play the viols… and generally having a whale of a time with what we had all thought (if we had thought about it at all) dull pedant’s music.

NASA physicist Ralph Kodis remembers meeting Dart (excerpt from a 2006 e-mail):

I think it was in 1954 while I was teaching at Harvard that Thurston Dart visited for a semester and gave a series of wonderful concerts at Harvard’s Fogg Museum.

I was an immediate convert, sold my piano, and began harpsichord lessons at the Longy School of Music. Then in 1955 I was awarded a National Science Foundation fellowship to conduct research with colleagues at Cambridge University.

As soon as I got settled, I wandered around the campus to see if I could find Thurston Dart’s digs. It didn’t take long, and brash young American that I was, I knocked on his door. He graciously invited me in (what a wonderful collection of early instruments he had), offered me a sherry, and I told him how much his Harvard concerts had impressed me. Would he, I asked, be willing to give me some lessons while I was in Cambridge? He replied that he was too busy with teaching and concert preparation to take on a beginner.

However, perhaps a friend of his, Mary Potts, would be interested. So with a note of introduction, I called on Mary, and we hit it off at once.

In the second post (due 12/9/11), there will be more Dart recordings, including a slice from Tom Goff’s Royal Festival Hall harpsichord jamborees and a comparison of Dart’s Froberger playing with that of his good friend, Gustav Leonhardt.

Any comments so far?

Arnold Dolmetsch with his family in 1932. Reproduced by kind permission of the University of Melbourne, [Percy] Grainger Museum. For full details see here.

I mentioned in my last post that Mary Potts is remembered only in her obituaries, the most complete of which was published in The Bulletin, the house journal of the Dolmetsch Foundation, which did not gain wide circulation.

Arnold Dolmetsch taught Mary the harpsichord from 1927, while she was still at the Royal College of Music. And Mary kept in touch with Arnold until at least 1938, when she wrote him a note – in perfect French – regretting that he had had to cancel a lesson with her due to illness.

I think that most people in the UK are familiar with the name Dolmetsch, if only as the name stamped on the plastic recorders we all squawked through at primary school. But how famous is Arnold Dolmetsch today, and to what extent is his contribution to the development of early music appreciated by the average concert-goer?

Arnold Dolmetsch brought much music and many instruments back from the dead, including the recorder – see article – and used both originals and copies he made himself in concerts in which he and his family usually dressed up in the costume of the period from which the music came.

Dolmetsch often gave concerts and instrument demonstrations when he lived in London, and was a part-time violin teacher at Dulwich College. His friends and admirers, at that time, included such famous names as William Morris, Selwyn Image, Roger Fry, Gabriele d’Annunzio, George Bernard Shaw, Ezra Pound, to whom he sold a clavichord, and George Moore, whose novel Evelyn Innes celebrates Dolmetsch’s life and work.

What he did was not always to everyone’s taste, and he was regularly slammed by the critics. In one review, the performance of a piece for two viols was described as sounding like “toothache calling unto toothache”.

Despite this, he continued to have a strong following, established the Haslemere Festival in 1925, started an instrument-making dynasty, and ended up with a state pension for his services to music. Although there’s now a substantial website, Personal Recollections of Arnold Dolmetsch, by his third wife, Mabel Dolmetsch, wasn’t published till 1958 and Margaret Campbell’s comprehensive biography, Dolmetsch: the Man and his Work, didn’t appear until 35 years after his death.

Here (press the play button after “Plage 12 : duree= 00:03:13”)

you can hear Arnold, obviously recorded in just one take, playing a Bach Prelude & Fugue on his own clavichord – with quite some force – back in 1930 (complete with chips frying in the background).

I have spoken to one person who, as a small boy, was taken to Arnold’s 80th birthday party, but I wonder if there are any other people who remember meeting him, or seeing him at concerts or elsewhere. He didn’t die till 1940, so it could just be possible, couldn’t it?

If you were there, then, or have any Dolmetsch memorabilia, please do get in touch!

Here’s the only known film of Arnold – with the beard – and his family. The young man playing the spinet is Rudolph Dolmetsch, who also gave Mary lessons, and was killed at sea in 1942. Mary remained close with Millicent, Rudolph’s widow (1906-1988), who played the viola da gamba. Apparently, they transcribed much unknown repertoire from the British Museum and other libraries, and gave many concerts together.

The dancing lady in the film is Mabel, Arnold’s third wife. She survived him by 23 years and was still living at Haslemere when Layton Ring came there as an apprentice in the 1950s.

Full details of this film here.

Also of interest:

The Dolmetsch Family with Diana Poulton: Pioneer Early Music Recordings, volume 1 (See blog post) Recordings, mostly from the 1930s, of Arnold, his third wife, Mabel, their children and musical friends playing small ensembles and viol and recorder consorts by the Lawes brothers, Purcell, Dowland, Marais, Leclair and others. This CD is not available in record shops, but you can order it here.

Copyright © 2011 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

Early Music (i.e. music up to around 1800) started to become more widely popular after World War II. This blog will primarily be about the pioneers who re-discovered this repertoire and started playing it on original instruments, or modern copies, in the authentic style, which is now often called historically informed performance, or HIP for short.

Why now?

The idea for this blog has grown out of research into the life of my harpsichord teacher, Mrs Mary Potts of Cambridge – herself a student of über-pioneer Arnold Dolmetsch, back in the 1920s. Apart from a tiny entry in a musical Who’s Who, her obituaries and a couple of mentions by now-famous students, I could find nothing at all about her. Continue reading The Early Music revival, does anyone still care?

|

Email subscription This feature is no longer available.

|