I didn’t know that the Bishop of Durham’s former residence at Auckland Castle, in Bishop Auckland (yes, really), had been bought by a millionaire – until I started to research visiting there, as a possible day trip, last summer.

The initial draw for the new owner was keeping together a set of thirteen stupendously large biblical oil paintings with a price tag of £15 million. Ultimately, he ended up buying the whole castle and the 800-year-old estate as well; see the full story here.

Prince Charles talks here (on video) about Auckland Castle

Surprisingly, there was nothing on the new glossy website about there being an organ. Once inside the ancient chapel, however, it didn’t take me long to notice that there was what looked like an impressive seventeenth-century pipe organ perched on the back wall, but maybe – as in the chapel of Durham Castle – it was just an old case.

All anyone could only tell me was that the organ was still used for services. At the ticket counter, though, they managed to rustle up a copy of a booklet (reprinted from the Church Quarterly Review, in 1935) by Canon C.K. Pattinson, called The Father Smith Organ in Auckland Castle.

The organ superstar of the seventeenth century

Bernard “Father” Smith was born as Bernhard Schmidt in Germany in around 1630, and was trained there as a master organ builder. At a certain point, he moved to Holland, where he became Barend Smit and, in 1663, built the sensational organ in the Grote Kerk in Edam. See also this article.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

In 1667 he emigrated to England and anglicized his name. The organ historian, Stephen Bicknell, suggested that this career move was in order to profit from the rebuilding of London churches, following the Great Fire in 1666. There was certainly a shortage of organ builders in England during and after the Commonwealth, as a result of the destruction of church organs by the Puritans. Sir John Hawkins noted, in his General History … of Music in 1776:

the makers of those instruments [organs] were necessitated to seek elsewhere than in the church for employment; many went abroad, and others … became joiners and carpenters, and mixed unnoticed with … those trades.

See also this fascinating dissertation: The Pipe Organ in Early Modern England by C.W. Cagle.

After around ten years in royal service Smith was formally appointed King Charles II’s “organ maker in ordinary” in 1681 and as such – according to Pattinson – occupied apartments in Whitehall with a salary of £20 a year.

Battle of the Organs

Smith was the most successful organ builder of his time, and beat his arch-rival, Renatus Harris, in the famous Battle of the Organs held in 1684, which was to decide who should get the contract for the new organ in the Temple Church in London. The fact that Smith employed John Blow and Henry Purcell to demonstrate the capabilities of his organ, which he had specially erected in the church, clearly didn’t hurt his cause.

Apart from making the organ which was the prize in this contest, Smith also built instruments for Westminster Abbey, St Paul’s Cathedral, Durham Cathedral, the chapel at Windsor Castle and many other churches.

The gift of a Bishop

The organ at Auckland Castle Chapel was specially built for this location in 1688, as a gift from Nathaniel, Lord Crewe, who was the Bishop of Durham from 1674 to 1721.

Although there’s no documentation, which is apparently common with gifts, the Crewe family crest is incorporated into the case decoration, and a slightly cryptic Latin inscription (not shown on the photo above) states that it was given by Nathaniel, Bishop of Durham, and refers to his previous post as Bishop of Oxford.

Is it really a Father Smith?

Pattinson mentions a “tradition” that the organ was by Smith, but there are no documents to support this either and, as Bicknell wryly comments, there are as many organs attributed to Father Smith as beds which were supposedly slept in by Queen Elizabeth I.

However, local organ adviser Richard Hird, who has written an excellent web page on this instrument, giving the current specification and details of the organ’s chequered history, makes a strong case for Smith:

- The Bishop was the secular as well as the religious head of the Palatinate of Durham, a state within the kingdom, which had been largely reinstated after the Commonwealth.

- Much of his time was spent in London – living at Durham House on the Strand – and moving and working in Court and government circles. He was a member of Charles II’s High Commission and was “prepared to go [to] all lengths with the Court”.

- Smith had already built the Durham Cathedral organ just a few years before (for which a contract and letters exist), which the Bishop would have known well.

- Therefore, the organ could not have been built by anyone other than the “royal organ maker”.

In addition, Cecil Clutton observed that Lord Crewe was a man “for whom the best was just good enough”.

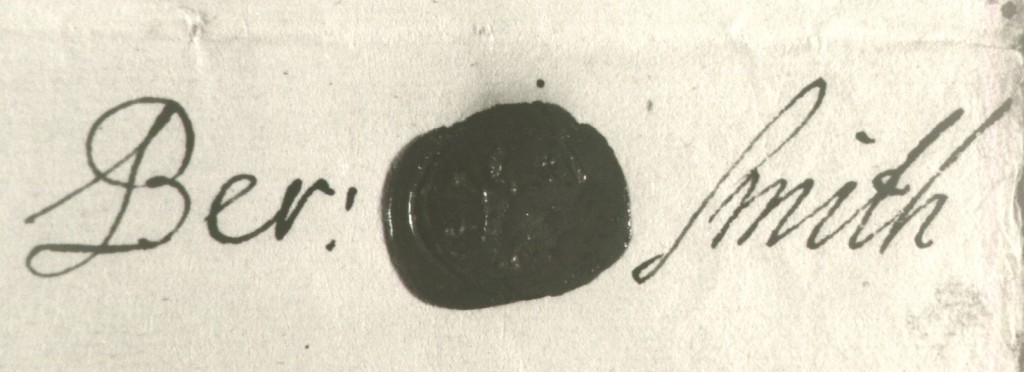

The organ case is also very Smith-like, according to early organ expert Dominic Gywnn. And, in an entry in his diary in 1826, the organ builder Alexander Buckingham, who worked on the instrument himself, wrote:

The original maker was Father Smith in 1680 [perhaps a slip of the pen, as 1688 is carved on the case] … names incl. “Mr Smith, organ maker” are wrote on the back of the organ.

These “signatures” have since disappeared.

Even though the organ, in its current state, is a 1903 Harrison & Harrison two-manual and pedal rebuild of a single-keyboard seventeenth-century instrument – which no longer has its original insides (and the internal layout has been rotated 90 degrees and the console is now on the side, not at the back) – it does still have mechanical action, all the pipes from five of the six original stops, the original reverse keyboard and even the ebony stop knobs, as shown below.

The console of the 1903 Harrison & Harrison organ at Auckland Castle, showing the original Father Smith reverse keyboard and five of the six original square-shanked ebony stop knobs (on the right) © Richard Hird

Harrison & Harrison’s records give detailed proposals for the renovation and rebuild, and state that the voicing of the old pipework was “to be respected”, and has not been changed.

You can judge for yourself to what extent this is an original-sounding organ, in the pieces played below by Alan Cuckston, using only the Father Smith stops (which are specified next to each title).

Tomkins – Fancy in A (Stopped Diapason)

Handel – Fantasia in C (Stopped Diapason, 15th)

Purcell – Toccata in A (Stopped Diapason, Principal, 15th)

Croft – Voluntary in A minor (Full Organ)

Despite these many changes, this instrument is still very important, as it is one of very few Father Smith organs that is in playing order, albeit in altered form.

Thanks are due to Richard Hird, for answering my many questions and for the photos; to Alan Cuckston, and to Peter Hill of Foxglove Audio, for giving permission to use their recordings of this organ; to Dominic Gywnn; and to Ian Lackenby, of Harrison & Harrison Ltd., for specially inspecting the organ on my behalf.

© Semibrevity 2013

I remember making the recording with Alan Cuckston way back. I do still have a digital copy if anyone is interested in a set of MP3 or WAV. Contact me at foxgloveaudio[at]gmail.com