If you’re a fan of Gustav Leonhardt and Frans Brüggen then you might just have heard of the Dutch recorder virtuoso Kees Otten; but he is not much acknowledged, even in Holland. Yet Otten was a musician of great importance for the emancipation of the recorder in Holland, its acceptance as a serious instrument in the concert hall, and the establishment of what we now call historically informed performance practice.

It was largely thanks to Otten’s tenacity (and, in part, the fact that J. S. Bach wrote recorder parts in his works) that the recorder was taken seriously by the Dutch Ministry of Education and given full status as a “proper” musical instrument.

Because of his influence, it began to be taught in schools for the first time, and from the mid 1950s it became possible to take a nationally recognized qualification in the recorder at Dutch conservatories. And this widespread recognition of the recorder, an instrument that is affordable and easy to play to a satisfying standard, helped early music to become established for amateurs in the Netherlands.

A dual musical life

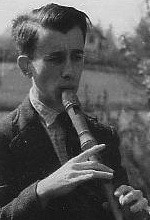

Kees Otten (1924–2008) came from a musical family: his mother was a piano teacher who gave lessons for more than 50 years, but it was his uncle, Willem van Warmelo, who taught him the recorder from 1930 to 1937 – “until I could play it better than he could!”, as Otten remarked – and laid the foundation for what was going to become his ultimate career.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

Van Warmelo, a music educator since the 1920s keen on the German idea of hausmusik (broadly speaking, domestic music-making), was one of the first to bring the recorder to Holland. He was friends with Poulenc and Hindemith, who shared his musical philosophy and, according to Otten, “used all kinds of music in his teaching method, not just old music”.

As it was impossible at that time to study the recorder as a “proper” instrument, Otten took up the clarinet and began classical training at the Amsterdam Muzieklyceum (Music Lyceum) in 1941. But it was jazz, particularly the music of Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton, that caught his imagination and, aged just 15, he had jammed – on the recorder! – with the great American jazz tenor saxophonist, Coleman Hawkins at a club in Amsterdam.

Listen to Otten improvising (on the recorder) at a jazz club in 1953

From 1942 he was playing in Bach cantatas conducted by the Bach-expert and harpsichordist Hans Brandts Buys, who was a major influence on Gustav Leonhardt. He was invariably joined by Joannes Collette (1918–1995) who is widely considered the first “real” recorder-player in Holland.

(Collette came from a famously fanatical early music family, where both parents and all five children played different instruments including recorders, a lute, a spinet and, by 1938, they also had a quartet of German-made viols.)

Not surprisingly, it was Brandts Buys, Otten and Collette who were the first people ever in Holland to perform the fourth Brandenburg Concerto with recorders instead of flutes, in a concert in the small hall of the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam.

Although he played baroque repertoire in semi-professional “underground” house-concerts, Otten continued to play jazz and “contemporary music” as a member of various cabaret groups, including the Canadian “liberators” band, the Sing Song Shakers.

His jazz breakthrough could have occurred in 1945, when he was offered a place in a well-known jazz orchestra by Kid Dynamite, for a 30-month tour of North Africa, the Balkans and Spain. But at this time he had a serious girlfriend, Marijke Ferguson (b. 1927; his student and his first wife, from 1950) and had been invited by Brandts Buys to take part in concerts and broadcasts of Bach cantatas. “After some hesitation”, said Otten, “I chose the girl and the Bach cantatas.”

So, in 1946 he was involved in the celebrations for the 25th anniversary of the Dutch Bach Society, performing in the Actus Tragicus (Bach’s Cantata BWV 106) conducted by Anthon van den Horst, and from 1947 onward he participated every year in the Society’s St Matthew Passion.

In the following years, he was to perform internationally with the lutenists Walter Gerwig (from 1952) and Julian Bream (whom he introduced to Holland in 1955), and in ensembles with Carl Dolmetsch (son of Arnold), among others. According to interviews, there were “lots” of concerts with these people, although only a handful are documented in what is probably Otten’s rather incomplete archive.

Here are various sound clips of Otten playing solos and in ensembles

His recorder teaching career began in 1947 at his old school, the Music Lyceum in Amsterdam and, by May 1954 – including groups at the local music school – he was teaching 130 students every week. He was so successful as a teacher that he was later to work at four Dutch conservatories simultaneously.

The Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble

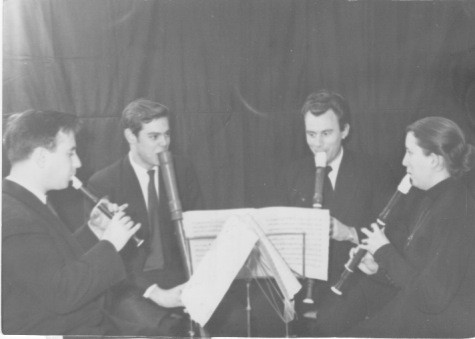

By 1948 Otten had established the Amsterdams Blokfluit Ensemble (Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble), then the only professional recorder group in Holland, which consisted of Marijke Ferguson, Frans Douwes and, later, his most famous pupil, Frans Brüggen (second from the left in the photo above). Occasionally they were accompanied by harpsichordist Jaap Spigt.

Interestingly, Jaap Spigt was so uncertain whether he should play with Otten at all – as the recorder at that time had the reputation of being a children’s toy – that he asked his teacher, Janny van Wering, at the time the foremost Dutch harpsichordist, who gave her blessing. Spigt’s relationship with Otten was to prove important for him, as it led to concert tours of the UK, where they played with Carl Dolmetsch, the important English recorder pioneer Edgar Hunt, and others; he was also to accompany Otten in his solo debut recital at the Concertgebouw in 1956, and in almost 90 other concerts. Spigt was later to become a noted choir conductor and was a harpsichord teacher on the staff of the Amsterdam conservatory at the same time as Leonhardt and Ton Koopman.

The repertoire of the Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble ranged from the 15th century through to the 20th and included many pieces specially written for Otten. He cleverly used these new works to promote the reputation of the recorder as a “proper” musical instrument to professional musicians. Also, the Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble’s extensive series of radio broadcasts (which included singers and other instrumentalists, including the young gamba-playing Gustav Leonhardt) and their many school concerts further helped to improve the recorder’s image, as something other than a child’s toy.

Looking at the programmes, you see works by Ibert, Rubbra and modern Dutch composers such as Henning and Zagwijn paired with madrigals, Praetorius, Handel and Purcell, plus a liberal helping of arrangements from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book and Bach’s keyboard music, particularly the Art of Fugue.

Otten was later to become a member of the first incarnation of the Leonhardt Consort, though only for a relatively short period, and to set up Muziekkring Obrecht and Syntagma Musicum, two important groups specialising in the performance of medieval and Renaissance music.

More about Otten in future blog posts.

Thanks are due to Marijke Ferguson, Marina Klunder (Kees Otten’s widow), and to Jolande van der Klis for her excellent book, Oude muziek in Nederland, which has been a valuable source in writing this post. The English translation of various quotes is my own.

Also of interest:

Muziekkring Obrecht – the first ever Dutch ensemble for medieval & Renaissance music

Frans Brüggen: the early years (1942–1959), with his teacher Kees Otten

The Leonhardt Consort: the early days – with recorder pioneer Kees Otten

Gustav Leonhardt & Martin Skowroneck – Making harpsichord history

Syntagma Musicum, the internationally famous Dutch early music group founded by Kees Otten

© Semibrevity 2014 – All rights reserved

[…] really the Dutch who are responsible for it’s return as a concert instrument. The efforts of Kees Otten (1924 – 2008), led to the elevation of the instrument’s status in the Netherlands, […]

This has been very interesting. I have just purchased a von Huene alto that was originally bought by Kees Otten in 1967. So I am looking forward to playing it when it arrives.