Martin Skowroneck has joked that if he could have afforded to buy a Dolmetsch recorder in 1948 or 1949, when he was a student flute teacher in Bremen, then perhaps he wouldn’t have started making musical instruments at all.

As it was, he was dissatisfied with the German-fingering “chair leg” recorders which were the only ones available to him, and determined to try to make something better, using a lathe cobbled together from US army surplus parts, which came with a stock of wood consisting of a bundle of maple baseball bats. That he was successful is evidenced by the fact that he was asked to make instruments for others, including a Hotteterre transverse flute (from the Berlin Musical Instrument Museum’s collection) for Professor Gustav Scheck, who played in the then-famous trio with harpsichordist Fritz Neumeyer and pioneer gamba-player August Wenzinger, who was also head of Schola Cantorum Basiliensis.

Skowroneck continued making flutes and recorders – initially from the baseball bats – until the early 1990s.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

Skowroneck’s first keyboards

In 1952 Skowroneck was asked to restore a Merzdorf clavichord, made in the 1930s, that had been badly damaged in the war; this led him to build two clavichords based on this instrument – one for himself and one for his sister – which he quickly discovered “had never existed in former times” (i.e. the 17th or 18th centuries). After two more clavichords, he built his first harpsichord in 1953.

Following a concert by the Scheck–Neumeyer–Wenzinger trio which “stirred me up thoroughly”, he had decided that if he was only ever going to build one harpsichord, then it should be a big one.

To get an idea of why they made such an impact on Skowroneck, here’s a sound clip from a recording made in November 1950, at low pitch, of Gustav Scheck, playing a transverse flute made by F.G.A. Kirst in Potsdam c. 1750, with Emil Seiler on a viola d’amore by Lupo, August Wenzinger on a 1657 Stainer viola da gamba and Fritz Neumeyer playing a Neupert harpsichord, “specially constructed to specifications by [Johann] Heinrich Silbermann”, in part of the final Allegro from

Telemann’s Sonata a tre in D major.

Skowroneck’s first attempt was a two-manual instrument with four sets of strings, including a 16–foot stop, based on the Berlin Musical Instrument Museum’s No. 316 (the so called “Bach-Harpsichord”) with elements of the museum’s No.5, probably by Gottfried Silbermann. This early Skowroneck is now also on display in the museum.

The Berlin Musical Instrument Museum was a key resource for Skowroneck in those early years. In his book Cembalobau/ Harpsichord Construction (in German and English), he writes about the kindness of the museum’s curator, Dr Alfred Berner, who gave him unlimited access, throughout the week, to handle and measure instruments, although the museum was then only officially open for two hours on a Saturday, for guided tours. This was effectively where Skowroneck learned the craft of making musical instruments based on historical examples. As Gustav Leonhardt later commented, “it could not be otherwise, because these are the only available teachers.”

A fateful weekend

In 1956, it was Dutch recorder pioneer Kees Otten who took Leonhardt, in a borrowed car, on a fateful road trip to Germany. In an interview given in 1974, Leonhardt recalled:

Hearing antique instruments in Vienna in the museum, and playing them – also in England – those belonging to Raymond Russell, for instance – made me realise that modern harpsichords were impossible. Then one day Kees Otten had heard of a wonderful flute maker named Martin Skowroneck, in Bremen. By chance we both had a free weekend and decided to drive there together to see him. At Skowroneck’s place I noticed there was a harpsichord in the room, as well as all the flutes — it was a revelation to me …

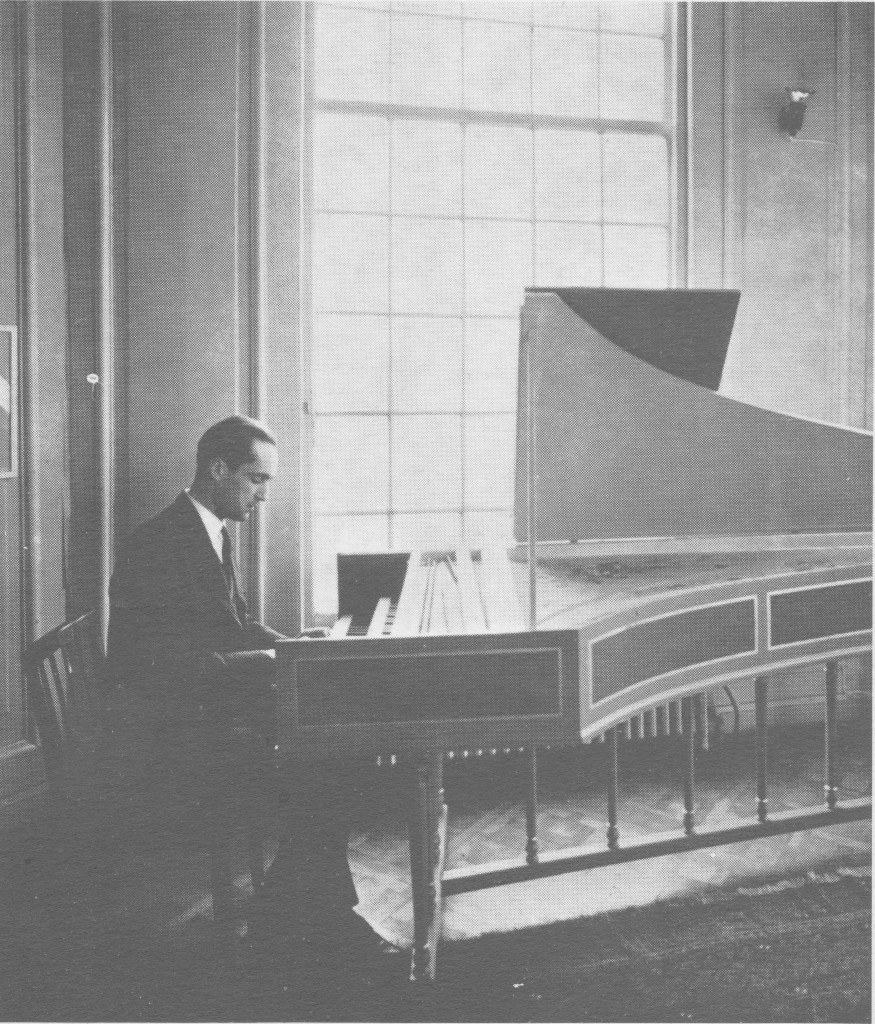

The instrument concerned was Skowroneck’s harpsichord No.5, built in 1955, in which he used a Ruckers construction, for the first time, with a correct soundboard layout. He says in his book, “The resulting sound gave me an important impetus [as] in spite of the backpost construction, it resembled an historical instrument.”

Although impressed, Leonhardt did not order an instrument for himself. Instead, he recommended Martin Skowroneck to the Harnoncourts, in Vienna, who were trying to find a harpsichord as lightly constructed as the historical stringed instruments they were playing in Concentus Musicus, which had just been founded in 1953.

As no plans or drawings were available, and few people had ever seen the inside of an old instrument, Skowroneck had some reservations about making a thin-walled, lightly braced Italian harpsichord, but was persuaded to attempt it by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who agreed to assume any financial risk should the structural integrity of the instrument fail.

In 1957 Skowroneck completed his No. 7: a one-manual harpsichord “after an Italian instrument of 1700”. This was his first truly historical harpsichord, and it can be heard in many of the recordings of Concentus Musicus from the 1960s and early 1970s. The initial disposition of 8′ 8′ 4′ was, however, not typical for the style and the 4′ register was later removed.

In the course of the next five years, Skowroneck built ten more Italian harpsichords, including a small, easy-to-carry version for Leonhardt in 1960. He also made twelve clavichords of various kinds and a two-manual Flemish harpsichord in 1961 which, although it has been used in recordings, has always stayed in the family.

A “quasi-Dulcken” for Leonhardt

In 1962, Leonhardt asked Skowroneck to make him an instrument based on two 2-manual harpsichords, by Joannes Daniel Dulcken, both built in 1745, belonging to museums in Washington and Vienna. Skowroneck also referred to the work of Dulcken’s contemporaries, particularly Joannes Petrus Bull, who had been his apprentice. The originals were built very much in the Flemish tradition of the Ruckers family, extended to a fully chromatic five-octave compass, and were 2.60 meters long.

Skowroneck describes below the information that he had to work with:

I had a few freehand sketches with measurements of the Dulcken harpsichord [in the Smithsonian Institute] in Washington [from Leonhardt] and some measurements of the Dulcken in Vienna [in the Kunsthistoriches Museum]. My little sketch contained some details of the inner construction, but I had no idea about the typical double case of the Dulcken. In Washington the double wall on the inside had erroneously been removed as not being original. This is only an indication of how little we knew at that time …

Some details of the original did not convince me, and I altered them. For instance, for my taste, the 8′ bridge was a little too close to the bentside in both the instruments. So I altered the form of the case somewhat. The result was, as I had to repeat far too often, an instrument close to Dulcken, but far from a copy.

Leonhardt’s “quasi-Dulcken” followed the original disposition of 8′ 8′ 4′ Nasal 8′, plus a buff stop, but was lighter, and had a completely different inner construction from the original (the photo on p. 139 of Cembalobau shows just how different it was). In total, Skowroneck made four Dulckens and it went on to become one of the most famous, and most copied, instruments in recent harpsichord history.

Leonhardt on the Dulcken in Böhm’s Keyboard Suite No. 8

The theme of re-creating historically plausible instruments, but not producing faithful copies, is very important to Skowroneck, and it permeates all the design and building principles outlined in his Cembalobau.

The single exception to his normal way of working is the 1755 fake Lefebvre harpsichord – which Skowroneck made for a bet with Leonhardt. Actually, this is his best documented instrument, as he himself wrote a very detailed article about its construction in the 2002 Galpin Society Journal.

Other opinions

Given that the first harpsichord kits made by piano-technician-turned-harpsichord-maker, Wolfgang Zuckermann, had no bentsides and were made of plywood, it’s curious that in his book, The Modern Harpsichord, written in 1969, he reveals his taste for authenticity. He writes warmly about Skowroneck’s instruments which “have flute-like (not silvery) trebles, reedy (not rustling) tenors, and sonorous (not booming) basses [as compared with German factory-made instruments of the time].”

According to Zuckermann, a Skowroneck harpsichord “does what the player, the listener and the music want it to do … it neither resists nor encourages its user, but mirrors precisely his own strengths and weaknesses … a characteristic which was also found in the Ruckers instruments of old.”

Much more recently, in September 2013, the eminent American harpsichord builder, John Phillips, said in an interview that “Skowroneck [was] one of my idols … I encountered some of his instruments early on, and they were different from anything I had heard before. They never overwhelmed you with sheer beauty of sound. They were players’ instruments, a tool for genuine music-making …”

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Tilman Skowroneck, and to his parents, for permission to use their copyright material and also for assembling information specially for this blog post.

Sad news, received since this blog post was published

Martin Skowroneck passed away on 14 May 2014, at the age of 87.

Martin Skowroneck was making harpsichords till the very end of his life. He always worked alone, and no doubt subscribed to the view of Johann Ludwig Dulcken (J.D.D.’s grandson) – which he once mentioned in a sleeve-note – that “the completing of an instrument must remain in one pair of hands”.

© Semibrevity 2014 – All rights reserved

Also of interest:

The Leonhardt Consort: the early days – with recorder pioneer Kees Otten

REQUEST FOR INFORMATION

Leonhardt’s instruments and the Leonhardt Consort

For future blog posts, I’m trying to discover when Leonhardt owned which instruments (antique or otherwise) and also to re-construct the concert performing history of the Leonhardt Consort.

If you know anything about either, or could suggest other people or possible sources, please get in touch by using the Comments Box below. Your reply will not appear on the blog.

Thanks for another extremely interesting blog post. I agree that the 1962 was a ‘game changer’, and I have always speculated that this instrument transformed Leonhardt’s playing. It has certain characteristics of sound and touch that he took full advantage of in his many recordings on it, and it is interesting that he chose to record repertoire as varied as Bach, Scarlatti and d’Anglebert on it. I have also wondered whether the delivery of the instrument in 1962, and Leonhardt’s breakthrough (in musical terms) recording of Froberger on a Ruckers the same year, were pure coincidence. Did Leonhardt learn things from this Dulcken ‘copy’ which he put to good use on the Ruckers? Perhaps Tilman or his father can tell us whether the Dulcken was actually delivered before the Froberger recording.

Leonhardt’s Dulcken is now owned by Bob van Asperen, who has recorded Bach and Scarlatti on it.

Regardless of how the Dulcken may have changed Leonhardt’s playing, he had owned original instruments himself, certainly since the late 1950s (if not before), and by 1962 would have been very familiar with using them. As Janny van Wering, Holland’s most respected harpsichordist at the time, had commented in around 1954, “Leonhardt … had studied and compared historical instruments in museums … He had the money to buy old instruments, and also the brains to realize that he had to be quick about it.”

The Froberger wasn’t, in fact, Leonhardt’s first recording on an original instrument. He’d previously made an EP for CNR (HV 514) in 1958 called “Girolamo Frescobaldi – Music for Harpsichord”, consisting of two toccatas and a fantasia, for which he, incongruently, used the 1766 Kirckman in Amerongen Castle in Holland.

Martin Skowroneck (1926-2014) passed away today, May 14, 2014, in the morning in Bremen

See //skowroneck.wordpress.com/2014/05/14/martin-skowroneck-1926-2014/