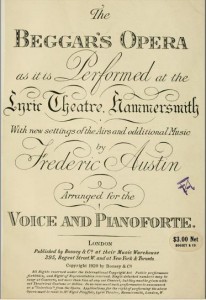

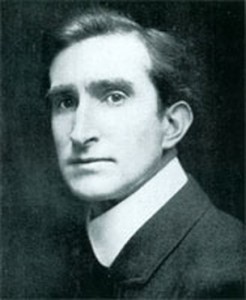

In May 1920, the opera singer Frederic Austin (1872 – 1952) went to see Nigel Playfair and, over tea and biscuits, they devised the idea of staging a revival of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera, which had not been produced in London since 1886.

Playfair knew some of the songs from childhood, and Austin was familiar with much eighteenth-century repertoire, as he had also been a professor of harmony and counterpoint at Liverpool. There and then, he played through an old score that Playfair had, “arranged by good Pepusch with figured basses and all” and, according to Playfair, he “jumped at the idea” of making an updated version.

Austin had just formally retired from the operatic stage, having sung the role of Count Almaviva in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, for Sir Thomas Beecham at Covent Garden. Due to financial problems, the Beecham Opera Company had closed its doors and so he, and the rest of the singers, were unemployed. The three men knew each other well, as Playfair had produced several operas for Beecham, including this last Figaro; he had also produced plays at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Playfair was a lawyer-turned-actor-manager who, with his business partner, the playwright, Arnold Bennett, had taken over the lease of the then unfashionable Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith (London), known locally as the “old Blood-and-Flea-Pit”. He needed a new project, and some singers, and Austin and his Beecham colleagues needed new jobs, so it was a marriage made in heaven.

The music

Although Pepusch had added harmony and scored the work for the theatre, it was Gay, who had a “good ear” and was a flautist, who chose the “tunes” to be used. He fitted his own lyrics to some of the most popular songs of the day, which were mainly of English, Scottish, Irish, Italian and French origin, and they mostly came from Thomas D’Urfey’s Wit and Mirth, or Pills to Purge Melancholy, published in 1719.

Although Pepusch had added harmony and scored the work for the theatre, it was Gay, who had a “good ear” and was a flautist, who chose the “tunes” to be used. He fitted his own lyrics to some of the most popular songs of the day, which were mainly of English, Scottish, Irish, Italian and French origin, and they mostly came from Thomas D’Urfey’s Wit and Mirth, or Pills to Purge Melancholy, published in 1719.

Nellie Chaplin, writing in Music and Letters in July 1922:

The unprecedented success of the Beggar’s Opera is due to the old tunes, which are in our blood. Clever as Mr. Gay’s libretto is, if Dr. Pepusch had written the “tunes” it would not have had the same hold on the public.

And Austin certainly agreed with her, as he discarded Pepusch’s work completely and used the tunes as raw material for what is, in effect, a new work made on the general plan of the old one … while keeping the atmosphere of the play and the period … turning solos into duets or more extended concerted pieces, inserting dances, instrumental interludes, and so on.

Austin himself couldn’t, quite, stop singing and he took the role of Peachum, for some time.

Nevertheless, the Musical Times review published in July, 1920 said that “the revival is thoroughly respectful to this intriguing old opera …” even though Arnold Bennett had extensively revised and bowdlerized the text, and the musical arrangement was brand new!

Nellie and her sisters

Frederic Austin:

It occurred to me also that it would be interesting to use the harpsichord and the “gamboys” [sic: gambas] … and I remembered those indefatigable propagandists of ancient music, the Misses Chaplin. They duly became the nucleus of the Hammersmith [ladies’] orchestra.

The Chaplin Trio, consisting of Nellie, Kate and Mabel Chaplin, had established themselves as a pre-eminent ladies’ ensemble, a well-known “brand”, playing both conventional classical repertoire and, from 1904, “ancient music and dances”, on authentic instruments. (Search on “Chaplin” to these previous blog posts in this series).

According to Playfair, writing in The Story of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith:

Nellie Chaplin and her sisters, and the orchestra, worked with us; for it is to be noted that from the first conception of the production to the first performance there was only possible an interval of five weeks!

[The Chaplins’] popularity with our audiences was unbounded, and a tribute, I am sure, to the great work which they have done for many years past in keeping up interest in our beautiful old English music.

The members of the Hammersmith Ladies’ Orchestra:

Nellie Chaplin harpsichord

Kate Chaplin 1st violin & viola d’amore

Mabel Chaplin cello & viola da gamba

Kathleen Thomas 2nd violin

Leila Bull oboe

Florence Mukle flute

Lilian Mukle viola

Louise Mukle double bass

We know nothing of Kathleen Thomas, except that she was described in the Tablet as being “a very capable young student of the Royal Academy, [who] gave her first violin recital at the Queen’s Hall …” But there’s a whole article (in German) about Leila Bull, whom the Musical Times noted as having “praiseworthy skill and intelligence”.

Florence, Louise, and Lilian Mukle were three of the five musical daughters of Ann Ford Mukle, a concert pianist, and Leopold Mukle, a German clockmaker from the Black Forest who was the inventor of the world’s first coin-operated juke-box, the Orchestrion.

An eighteenth-century blockbuster

The production was an instant success, due to the “tunes”, the quality of the singing, the humour (much needed, just 18 months after the Armistice) and the spare, evocative design, with just a “hint at the eighteenth-century” (due to financial constraints), which The Spectator described as “ a perfect little Hogarth [engraving]. Mr. [Claud] Lovat Fraser’s costumes and setting are beyond praise”.

The production was an instant success, due to the “tunes”, the quality of the singing, the humour (much needed, just 18 months after the Armistice) and the spare, evocative design, with just a “hint at the eighteenth-century” (due to financial constraints), which The Spectator described as “ a perfect little Hogarth [engraving]. Mr. [Claud] Lovat Fraser’s costumes and setting are beyond praise”.

According to Jeremy Barlow, who has done extensive research on the The Beggar’s Opera and made his own “authentic” edition, published by OUP (realizing Pepusch’s “ungainly basses”), Austin’s version was the most popular of the 20th century. He goes on to say that the use of of harpsichord, viola d’ amore, and viola da gamba was “quite novel in the 1920s, and must have given the work a convincing period flavour at the time. Austin’s arrangement now has its own period charm, evoking musical comedy of the 1920s rather than ballad opera in the 18th century.”

Recording of Austin’s version of the Beggar’s Opera, at Glyndebourne, conducted by Michael Mudie, in April 1940

At the end of the first record-breaking run of 1463 consecutive performances (which lasted for three and a half years, ending on 17 December 1923), the production had provided “a fortune” for the theatre, and had been seen by almost three quarters of a million people!

The popularity of the production was such that gramophone records, featuring members of the original cast, and the Chaplin sisters, were produced in 1922. Figurines in porcelain and wax of the main characters were also made in large numbers, including a series by the famous factory, Royal Doulton. The subsequent re-runs, in 1925, 1926, 1928, 1929 and 1930, amounting to 241 performances, added a further 120,000 people to the total.

The end of the Chaplin Trio

Nellie Chaplin died on 16 April, 1930, and her pupil, Margaret Hodsdon, took over as harpsichordist of the ladies’ orchestra for the final run, from 13 May 1930 to 21 June 1930. The review in The Times, 14 May 1930 mentioned Nellie’s demise and said that “her sisters continue to play the viola d’amour [sic] and the viola da gamba.”

According to The Times, 14 November 1932:

Much of the success of the Chaplin Trio in the past was due to Miss Nellie Chaplin, whose death deprived the sisters of their leader, and to whose musicianship they owed their repertory and the special character of their performance.

Nevertheless, the sisters tried to keep the family business going, and a promotional leaflet was made called, “The late Nellie Chaplin’s Ancient Dances and Music”, announcing many musical options and introducing Margaret Hodsdon, “a pupil of the late Nellie Chaplin”, as their new harpsichordist. The fact, though, that there are only two references to her having played together with the Chaplin sisters in concerts: in October 1931 and November 1932, rather suggests that the “great big gap” Kate Chaplin had spoken of to Percy Scholes (see here) just couldn’t be filled.

After that, either the Chaplins stopped performing completely or they continued with low-level undocumented “at homes”, garden parties and school concerts, which were advertised in that leaflet. We’ll never really know for certain.

None of the sisters ever married, and they lived together all their lives, first in the parental home – until their mother died in 1910 – and then just the three of them, with a live-in servant and a “boarder”. Kate and Mabel spent their latter years, from 1939, in Finchley, north London, with their widowed brother Charles Albert, and his daughter, Dorothy (a dancer, who had sometimes performed with them). Kate died in 1948 and Mabel passed away, aged 90, in 1960; she kept her Barak Norman bass viol with her till the very end.

In his obituary in The Strad, Nellie’s friend, the Belgian cellist, musicologist and writer, Edmund van der Straeten, wrote that “the laurel and ivy will entwine her name in the history of British musicians”. Sadly, this never happened, and Nellie and her sisters were, until very recently, completely forgotten.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jeremy Barlow, who first mentioned the Chaplin sisters to Semibrevity; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Professor Freia Hoffmann of the Sophie Drinker Institut in Bremen, who kindly shared her very extensive research; Sandy Mitchell; and Michael Mullen and Elizabeth Wells of the Royal College of Music.

I’ve just found this, in my researches for a biography of Frederic Austin – who was my grandfather.. It’s very interesting, and filled in some gaps in my knowledge of the production

I have had the early 78rpm discs for decades, and in a talk about early harpsichord recordings, I played an excerpt where the harpsichord is (somehat) audible (‘O Polly you might have toy’d and kiss’d’) from HMV D524, that particular side recorded in December 1920.

My talk was given back in 1990! So the Chaplins were not ‘until very recently, completely forgotten’ 🙂

But it’s wonderful to have access to so much more information these days; it was very hard work finding anything about the Chaplins over 30 years ago.