By Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

Scholarship and spectacle

There is a fragrant air about the concerts of old music that the Misses Chaplin give… But the romantic appeal of the old instruments and the old manner of presenting music does not banish scholarly accuracy on the one hand nor more specifically musical pleasure on the other.

This Times reviewer, writing in October 1927, exposes a tension between scholarship and entertainment in the Chaplins’ presentation of early music. First, the programmes needed popular appeal and had to be performable rather than historically accurate in every detail; second, musicology was a relatively young field, and much academic knowledge that musicians take for granted today simply wasn’t accessible. Although so many of Nellie’s events sailed under the flag of “ancient dances and music”, they occasionally included new or contemporary works based on old tunes or poems alongside works by Byrd, Morley or Purcell. Several examples appear in the records of the Oriana Madrigal Society, founded in 1904 to promote the performance of Elizabethan music. As well as the April 1916 concert mentioned here, on 19 December of that year, the Chaplin String Quartet plus a singer and oboist gave the first performance of Holst’s Four Old English Carols; while on 10–12 April 1919, a three-part concert illustrating “music and dance in Shakespeare’s time” included the first performances of Balfour Gardiner’s settings of two early English songs.

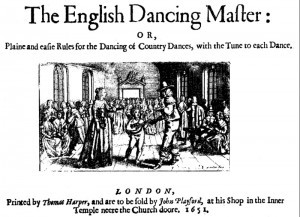

It is unlikely, then, that Nellie was seeking to establish “authentic” scores for the dances, though she owned a copy of Playford’s Dancing Master in an edition of 1665 and another of the 17th edition of 1716. She relates that one of her collaborators went to the British Museum to verify the original orchestration of a sarabande by André Destouches (1672–1749), which they were scoring from a solo piano version. But countless examples of pavans, galliards, allemandes, courantes and so on by familiar Renaissance and Baroque composers were in print at the time and, as the concert programmes and reviews show, provided the music for the court dances. The English pieces from Playford were “harmonized” for the Chaplins’ usual musical forces – strings old and new, oboe, and harpsichord – by a number of collaborators:

It is unlikely, then, that Nellie was seeking to establish “authentic” scores for the dances, though she owned a copy of Playford’s Dancing Master in an edition of 1665 and another of the 17th edition of 1716. She relates that one of her collaborators went to the British Museum to verify the original orchestration of a sarabande by André Destouches (1672–1749), which they were scoring from a solo piano version. But countless examples of pavans, galliards, allemandes, courantes and so on by familiar Renaissance and Baroque composers were in print at the time and, as the concert programmes and reviews show, provided the music for the court dances. The English pieces from Playford were “harmonized” for the Chaplins’ usual musical forces – strings old and new, oboe, and harpsichord – by a number of collaborators:

“All the tunes are written for the treble violin alone. They are full of vitality, and further charm has been given them by the simple harmony which has been added for String Quartet and Oboe by Mr. R.L. Cox [and three others].”

Although the dances were mostly arranged by others, Nellie published three books on English dances. In 1909 the Curwen Press published her Ancient Dances and Music, a selection of six Playford dances, which went into further editions. In 1911 it published her Court Dances and Others: An invaluable guide to the manners and protocols of the dance floor with step guides and musical score for amongst others the Pavane, the Irish Jig and the Chacone, also from Playford. And 1913 saw the publication of a small book containing a minuet arranged by Carlo Coppi to music by Philip Hayes, and a gavotte arranged by Lucia Cormani (the teacher of her niece, Dorothy) to music by Thomas Arne, both dances “as arranged for Nellie Chaplin’s revival of Ancient Dances and Music at the Royal Albert Hall Theatre in 1904”.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

The Chaplins’ approach to early music could not be described as purist, rather as populist and “period”. Nellie was not a scholar like Edmund Fellowes or the editors of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book; but she was exploring something new, inspired by a sincere desire to widen the range of pre-Classical music and dance available to the early twentieth-century public.

Where Nellie was seeking authenticity was in the dance steps and figures, which she studiously copied and “traced” from the originals in museums. Her research into dance was extensive, and broke new ground, as she herself recognized:

I think I am justified in claiming the right of priority in reviving the Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, Chaconne. Canaries, Rigaudon, Passepied, Tambourin, Bourrée, Forlana, and the Galliard and Tourdion.

This work became important to the English folk dance and song revival movement spearheaded by Mary Neal, Clive Carey, and Cecil Sharp.

Spreading the message

Teaching was a large part of the professional lives of Nellie and her sisters. All three are described as teachers in the national census of 1911 and their teaching activities are mentioned from time to time in the records we have of them. Nellie opened her own Pianoforte Foundation School as early as 1893 and by 1907 ran a school of early and country dancing in London, as the newspaper advertisement on the right shows.

All three are described as teachers in the national census of 1911 and their teaching activities are mentioned from time to time in the records we have of them. Nellie opened her own Pianoforte Foundation School as early as 1893 and by 1907 ran a school of early and country dancing in London, as the newspaper advertisement on the right shows.

Young people were involved in the early dances both as performers and audience. Nellie was concerned that students were being taught to play Baroque music without ever seeing what the movements of the familiar suites were like when actually danced:

There is a special educational purpose in the revival of the dances of the suites, for young people are constantly taught to play Couperin, Bach, and Handel [without] a clear notion of what the actual rhythm of the dance measures is, and they cannot get the notion so readily by any other means as by seeing them danced, except indeed by dancing themselves. (The Times 27 November 1911)

She was also always ready with information about the harpsichord: in her 1922 article she writes that audience members very often came up to her after performances of The Beggar’s Opera to ask about the instrument, its mechanism, history, and playing technique. In 1911 she gave daily demonstrations of the harpsichord at a weeklong exhibition of modern and early keyboards, and over her long career provided the musical illustrations for many lecture-recitals on subjects such as the evolution of the piano and the Couperin family.

Coda: Nellie Chaplin, national treasure

Nellie clearly became a national treasure: according to a 1924 review, “the dances were in the hands of Miss Nellie Chaplin – praise is therefore superfluous.” When she died in April 1930, tributes poured in. Kate, replying to Percy Scholes, author of The Oxford Companion to Music, wrote touchingly that over 400 letters of condolence had arrived. “We have indeed lost a very dear and loving sister”, she wrote; “we were, as you know, such a devoted trio, and her passing has left a great big gap. She was so much loved, and her work was always so sincere.”

Among her obituaries, this one from the Morning Post of 19 April 1930 is typical: “Her unwearied and unselfish enthusiasm for the music of the past had an incalculable influence on the revival and preservation of its popularity.”

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jeremy Barlow, who first mentioned the Chaplin sisters to Semibrevity; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Professor Freia Hoffmann of the Sophie Drinker Institut in Bremen, who kindly shared her very extensive research; Sandy Mitchell; and Michael Mullen and Elizabeth Wells of the Royal College of Music.

© Mandy Macdonald 2017 – All rights reserved

Leave a Reply