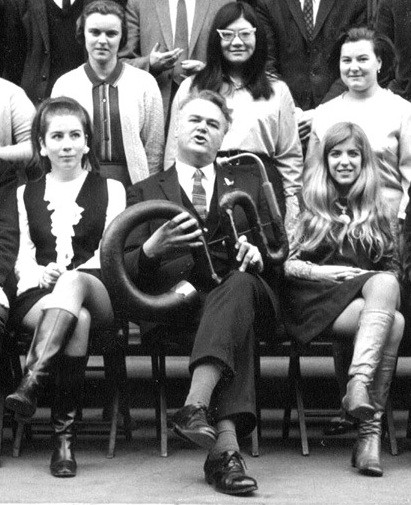

Music Faculty, King’s College, University of London, 1968. Reproduced by kind permission of King’s College London. Professor Thurston Dart (holding the serpent) was at the time King Edward Professor of Music and established the faculty in 1964.

The composer Michael Nyman well-known for his collaboration on Peter Greenaway’s films, is described on a movies website as being mentored as a PhD student by the “famed” Baroque scholar, Thurston Dart, at King’s College, London; but I wonder how famous Dart actually was then – and now, 40 years after his death. If the current CD catalogue is any indication, then “not very” is the answer.

From the 76 records Dart made, only two clavichord compilations (consisting largely of works by Froberger and Bach’s French Suites) are currently available, along with some English organ music, plus a little continuo tinkling for Anthony Lewis and, oddly, Klemperer with Schwarzkopf. His harpsichord recordings, and his work with the Philomusica, the re-named Boyd Neel Orchestra, which he took over until 1959, are all long gone.

Here’s Dart playing C.P.E. Bach’s Concerto in F Major Op. 7, No. 2 (W.C56) on an eighteenth century chamber organ with the Boyd Neel Orchestra on an LP from 1956.

Dart made many recordings for the L’Oiseau-Lyre label including Bach’s Orchestral Suites, the Triple Concerto, the Harpsichord Concertos, as well as Dowland’s Lachrymae, Handel’s Water Music, Couperin’s Pièces de violes and Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie. There was also lots of Purcell: one of his earliest recordings (on the French label BAM, made in 1956) was a disc of Purcell’s Trio Sonatas (1683) with him as leader of the Jacobean Ensemble, with Desmond Dupré on the gamba and violinists Neville Marriner and Peter Gibbs. Here’s the Gramophone review of this LP and a short extract.

TD NM PG DD

Does anyone know anything about Desmond Dupré? [Please comment below]

The dozens of lectures which Dart broadcast for the BBC have also all but disappeared, except in the memories of those who heard them. I have, though, been able to track down the first few chapters of his book on John Bull to a former student, Greg Holt, and a single recording, also on Bull, held by The British Library. Although there is now a Thurston Dart Professor at King’s College London, the books he bequeathed to their library can no longer be identified as ever having been his.

A memorial volume edited by Ian Bent, Source Materials and the Interpretation of Music (London, 1981), was published 10 years after Dart’s death. The six-page biographical sketch included there is almost all that is left of him, otherwise we have only Greg Holt’s recent biography (see next post), a couple of wikis, an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography and some obituaries.

His most lasting legacy would seem to be the three generations of musicologists he trained when he was at Cambridge and KCL. They include such famous names as Christopher Hogwood; the Bach and organ expert Peter Williams; Sir John Eliot Gardiner, who has recently called him “the Sherlock Holmes of musicology at the time”; the harpsichordist Davitt Moroney and Nigel Fortune, co-author of the Monteverdi Companion and long-term Grove editor. Nigel told me that Dart had the knack of getting his students to transcribe lute tablature and other early notation, so that he could judge if they were worth considering further.

Dart wrote only one book, the slim but seminal The Interpretation of Music (London, 1954) which, according to Harry Haskell in The Early Music Revival: A History, “heralded the new philosophy of historical performance that transformed the early music movement in the post-war period”.

His output, though, was prodigious in terms of the huge amount of completely unknown music that he edited (as well as revising earlier work by E. H. Fellowes) and the many articles he wrote in scholarly journals and elsewhere, not yet, apparently, all accounted for. I’m told that he was a charismatic speaker and inspired teacher.

Allen Percival, one of Dart’s students at Cambridge in the fifties, wrote:

Soon [Dart] had us playing Landini in what were then unheard-of realizations, singing nasal medieval songs, attempting to play the viols… and generally having a whale of a time with what we had all thought (if we had thought about it at all) dull pedant’s music.

NASA physicist Ralph Kodis remembers meeting Dart (excerpt from a 2006 e-mail):

I think it was in 1954 while I was teaching at Harvard that Thurston Dart visited for a semester and gave a series of wonderful concerts at Harvard’s Fogg Museum.

I was an immediate convert, sold my piano, and began harpsichord lessons at the Longy School of Music. Then in 1955 I was awarded a National Science Foundation fellowship to conduct research with colleagues at Cambridge University.

As soon as I got settled, I wandered around the campus to see if I could find Thurston Dart’s digs. It didn’t take long, and brash young American that I was, I knocked on his door. He graciously invited me in (what a wonderful collection of early instruments he had), offered me a sherry, and I told him how much his Harvard concerts had impressed me. Would he, I asked, be willing to give me some lessons while I was in Cambridge? He replied that he was too busy with teaching and concert preparation to take on a beginner.

However, perhaps a friend of his, Mary Potts, would be interested. So with a note of introduction, I called on Mary, and we hit it off at once.

It was probably September 1961 when I was about to start my third year reading music at Cambridge and my first under Dart’s supervision I listened to a fascinating talk he gave on the BBC Third Programme about a recently issued LP by Miles Davis, the jazz trumpeter. This album, entitled ‘Kind of Blue’, had attracted Dart’s attention because the material and the ‘Cool’ improvisations around it was conceived in terms of Modality rather than the traditional major/minor Blues tonality of the idiom. Dart applauded what he recognised to be a fruitful new trend in this particular branch of World Music. Already a fan of Miles Davis myself, and his pianist Bill Evans, at that time, I have wondered sometimes whether Dart himself kept up with these trends, or if someone else brought this particular music to his attention. The discourse in his rooms at Jesus College together with my fellow supervisee, Jerome Roche, was more or less confined to historical and paleographical matters. On contemporary music I recall him only once referring to Shostakovitch rather fondly as ‘Dmitri’.

Dear Alan Cuckston

I have just picked up your note on TD in June 2015.

I was Selwyn College Music Secretary in 1958, and TD was Senior Music Secretary. I fixed the usual recital which he provided for the regular Selwyn Sunday Evening Concerts, so we talked a few times.

Very amused to hear that he was keen on Kind of Blue and Bill Evans, whom I now worship. I sang in a EM group at Jesus, though with Brian Trowell, not Dart, I was already a very experienced practical musician reading Maths not Music, but Boris selected me to sing with his Cam. Mad Soc that year, although he had to hand over to Ray Leppard before term started) brought in to assist the rather rough music students of the time to get through early sung part music.

Pleased to discuss further via Email if you are interested.

Edward James

Dart’s memory lives on at St Lawrence’s Church, Appleby, Cumbria. The former organ of Carlisle Cathedral is situated here. It dates from 1661, but some parts may be older. During the 1950s Dart recorded a selection of 16th and 17th century compositions on the instrument which is said to be England’s oldest working parish church organ. Beside the organ was a poster, (October 2015), advertising CD copies of the recording, available from the nearby Tourist Information. [This is likely the 1994 re-issue of the LP originally published in 1958 which consists of music played on four historic organs.]

More recently (2021) there are nearly all of the Dart recordings on the Eloquence Label. Handel’s Water Music, Semele, Songs for Courtiers and Cavaliers and Cantatas of Handel and Scarlatti with Helen Watts. All in really good sound.