Fellowes’ life and legacy

Aided in the churchy sphere by Professor Sir Percy Buck, who was one of his oldest friends (and a teacher of Mary Potts at the RCM), Edmund Fellowes brought about a revolution, albeit a gentle one: he both changed the way in which choral and other early music was understood and raised the quality of performance exponentially within his own lifetime. Fellowes was a scholar–performer before we knew the word.

Despite the fact that his name often appears in footnotes, and there is an entry for him in Grove, his contribution to the revival of old English music and performance practice hasn’t been much appreciated since Sylvia Townsend Warner wrote about his tenacious detective-work, describing him as “inexhaustible and obstinately conscientious”, in an article that was printed alongside his obituary.

Sixty years after his death, pretty much all we know about him comes from his autobiography published in 1946.

A charmed childhood

In his book, modestly called Memoirs of an Amateur Musician, Fellowes gives an amazingly detailed account of his very well-to-do and cultured background, which involved staging French plays at home and going to concerts given by people like Rubenstein, Liszt and Clara Schumann.

His mother was one of the best amateur players of the time. She had been taught piano by Julius Benedict and singing by Manuel García, founder of the famous García School of Singing, and sometime teacher of his famous sisters: Pauline Viardot-García and Maria Malibran (who was recently celebrated by Cecilia Bartoli).

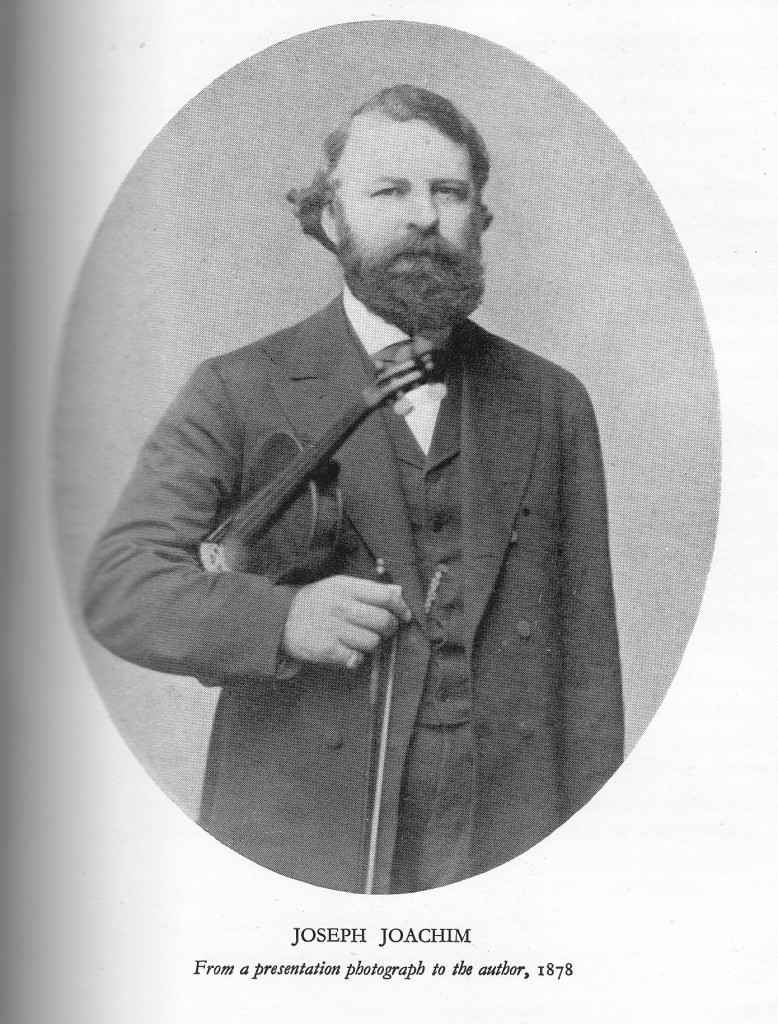

Fellowes had piano lessons, with his mother, from the age of five, and began the violin at six, getting three lessons a week; so he made good progress before going to school, which didn’t happen, apparently, till he was nine. By his own reckoning, he was not yet seven and a half when he met and played for the famous violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim, who offered to take the young Edmund as a private student in Berlin. This great opportunity was declined “so that I might not leave the conventional lines of a English boy’s education”.

Here’s Joachim playing Bach’s Adagio in G minor, in 1904.

The Amati violin

Around the same time, the 1679 “Stevens” Amati violin (which had belonged to R.J.S. Stevens, glee-writer and organist of Charterhouse) was bought for him by the husband of a cousin, for £100, “so that he would have a really good violin to play on when he grows up”. And he certainly put it to good use, playing chamber music throughout his life in public with professionals, starting at the age of 13.

Sadly, I’ve been unable to find any solo recordings of Fellowes playing the violin. But here he is in a string sextet, consisting of 2 violins, 2 violas and 2 cellos – which was the best approximation that they could make for a chest of viols – in 1923, Byrd’s tercentenary year. This is another sound file from CHARM.

William Byrd – Fantazia for String Sextet or small String Orchestra [from Psalms, Songs and Sonnets, no. 11, part 1], edited by E. H. Fellowes

Later life

Predictably, he went to Oxford, was ordained as a priest in 1894, and received his MA and B.Mus. degrees in 1896. After a stint as Precentor at Bristol Cathedral, he spent the rest of his life, from 1900 to his death in 1951, as a minor canon of St George’s Chapel, Windsor, “which allowed him the necessary leisure to pursue his interests in music, cricket [he published A History of Winchester Cricket in 1930] and genealogy”. See details of his spartan living conditions here.

He married Lilian Louisa Vesey Hamilton, the daughter of an admiral, in 1899.

To end with, here’s a lively madrigal recorded around 1930. Fellowes is conducting the St George’s Singers, about whom I know absolutely nothing.

Thomas Morley – Sing we and chant it

Next week: Fellowes’ greatest discovery and how irritation caused by Arnold Dolmetsch forced him to learn the lute.

MOLTO BELLO!!! Thank you for sharing this Great Biographical information.

I find this fascinating. I have good reason to believe that he was my great grandfather but have found no evidence online. I have good memories of a great aunt Rosalind and great uncle William who were both of brilliant character, but of whom I was too young to appreciate. They would have been his children. Can anyone enlighten me of them? It seems that William wrote an article about growing up in Cloisters, but I cannot seem to find it online.